At the NGV’s Making Good: Redesigning the Everyday, design becomes a force for repair. From algae-based vinyl to mycelium earplugs, the exhibition proves that rethinking the ordinary can reshape our collective future.

Installation image of the Making Good: Redesigning the Everyday exhibition, on display from 29 August to 1 February 2026 at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia. Photo: Eugene Hyland.

October 17th, 2025

“We’re surrounded by bad news and an existential fear about our future,” says Ewan McEoin, the Senior Curator of Contemporary Design and Architecture at the National Gallery of Victoria, as we stand at the entrance of Making Good: Redesigning the Everyday. On display until 1st February, 2026, this exhibition aims to counter this. It is “a show about good news,” says McEoin, that illustrates how “people are using their intelligence, creativity and entrepreneurship to fix things.”

It is also a show that invites the design industry, businesses and government to do better. The products and projects on display demonstrate that not only is it possible to design and make things that are less environmentally, socially, or culturally damaging, but it is also possible to design things that can actually help heal and restore.

Curated by Gemma Savio, Curator of Contemporary Design and Architecture, the exhibition brings together 56 objects across a broad range of categories, including fashion and textiles, food, healthcare, construction, graphic design and new materials. It is deliberately broad in scope while focusing on projects that can be scaled up to have significant impact. It aims to introduce audiences to the concept of regenerative design while setting the stage for a future exhibition series that focuses on design that heals.

In this Q&A, McEoin walks Indesignlive through the exhibition, explaining the objects on display and how they illustrate important shifts in how we think about design, society, consumption and consumerism.

What prompted this exhibition?

We are at a moment in history where we are more fully understanding the unintended consequences that the designs of the last century have had and are having. As we become more familiar with things like the climate emergency, reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, or the rising awareness of neurodivergence, we can definitely see the lack of those things having been addressed in design historically.

How did the design industry get to a point of more awareness around these things?

We’ve gone through phases in design. First, we’ve been unaware of harm – this happened due to very long supply chains that lack transparency and a lack of the real consequences of using materials like petrochemical-based plastics. We didn’t know that these things would reach the scale and complexity they have.

Then, as these hidden harms have become more evident, we’ve been trying to address them. The last 20 years or so have been marked by the idea of design trying to reduce harm, so reusing, recycling, and reducing waste. But really, for the world to be where it needs to be in the next 100 years, we need to repair. So the open question this exhibition asks is: does design have the capacity to heal and repair? And if it does, what do we need to do to get there?

Related: Fletcher Arts October group show returns to Toorak

What do you hope people will take away from this exhibition?

I suppose it’s an invitation to be positive. What you get from it is the feeling of ‘My God, every single thing has to be redesigned!’ – that is a massive job, but it’s also a massive opportunity.

We want to show that one product, at scale, can have either huge negative impacts or huge positive impacts. We’re living in a globalised economy where a large part of the economy is based on consumption. It doesn’t look like that’s going away, so we need to think about how things are swapped out. For example, one of the products on display from GOB Earth Inc. is an earplug made from mycelium. It asks: What would happen if something as simple as a disposable earplug were made from a 100% compostable material? How many millions of plastic earplugs would that divert from landfill a week?

Another train of thought on this idea of reducing impact could be that rather than changing the material, it’s better not to consume earplugs in the first place…

Maybe… and the exhibition is also asking us to remember not to introduce new products into the world that are going to do harm. If people had thought more thoroughly about the original disposable earplugs, maybe they would have never made them.

The unintended consequences of someone trying to do something that’s democratising or making something new often has short-term benefits of convenience but designers can no longer claim that they don’t know the consequences. We’ve heard that excuse for too long.

Can you highlight a few projects as we walk through the first section that you think are really successful examples of “making good”?

Let’s start with the FLOWRDWN puffer jacket from a brand called PANGIA in the UK. Usually, a puffer jacket is filled with the feathers of birds that generally have to die in the process of being de-feathered. While there might be a small group that are conscious of the ethics of animal rights in this scenario, its mostly a hidden problem because the down inside the product. This jacket, however, replaces the bird-based down with one made from wild flowers that have been grown through regenerative farming practices. The crops are insect-friendly, so there’s a multi-layered benefit.

So this product deals with the ethics of material supply chains and the environment. Other exhibits are more focused on social or labour ideas around making good, right?

Yes, other projects look at the way something is made, labour conditions or hyper consumption. We’re trying to get people to think about the many systems that we are part of and that damage happens all the way along the supply chain.

In terms of social impact, one project we are showing is swimwear from a brand called Rubies, who make garments for trans girls. It’s now commonly understood that trans people often experience body dysphoria, so the feeling of being completely uncomfortable in their body. This swimming costume, called The Sky No-Tuck Shaping One-Piece, is one of the few products in the world designed specifically for the anatomy of a trans girl to create the opportunity for them to confidently go swimming and just be a normal kid. What we love about this project is that it’s made by an entrepreneur with a transgender daughter, who launched this into the market from Canada and now sells it globally.

It’s interesting that those examples encourage you to look at ubiquitous everyday objects in a new way. It makes you realise that someone has designed them to be the way they are, so that means that someone can redesign them better or differently.

Yes, along the same lines as that is the Hoopsy eco pregnancy test, which is basically a fully recyclable paper-based pregnancy test. When we think about what a pregnancy test normally looks like, it’s completely plastic. This one is discreet, easy to dispose of, completely biodegradable and can be buried. We live in a world with tons of medical products, especially with things like COVID, so single-use plastic medical devices are a huge source of problematic waste and this shows an alternative.

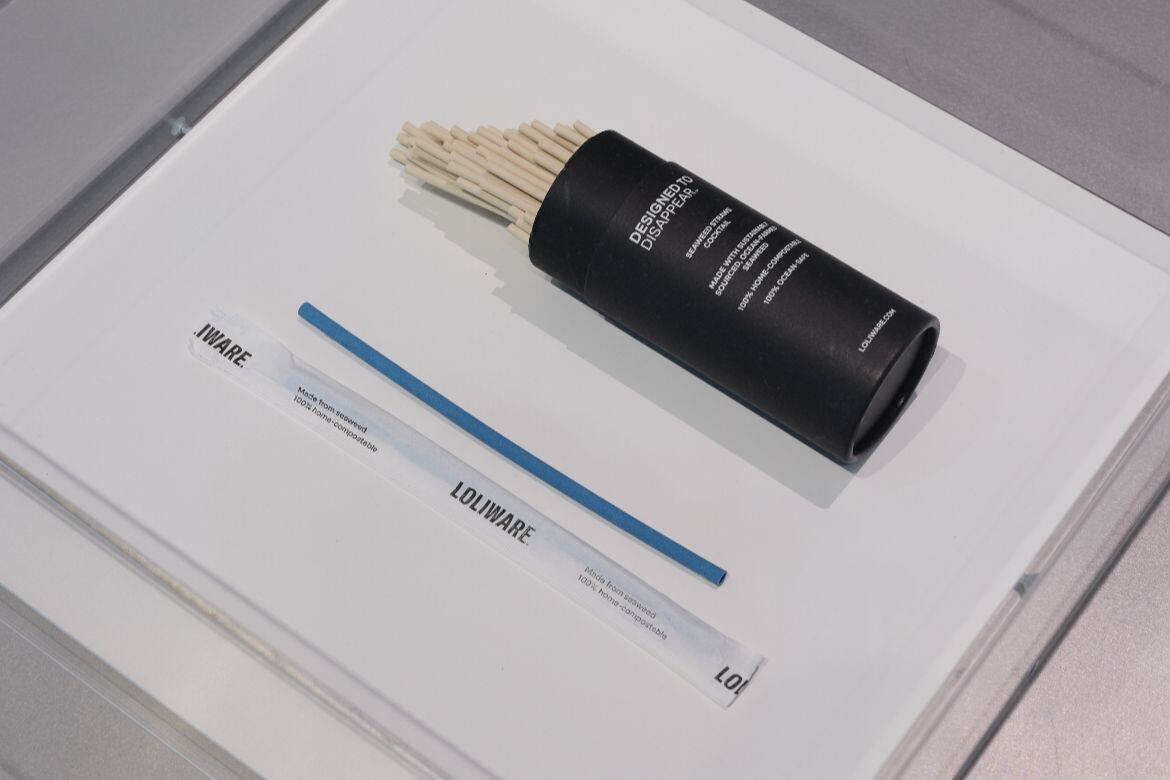

We also have examples of bio materials being developed to replace plastic use, which will be really impactful when scaled. There is a rice-husk-based lunchbox by Charles Wilson and Andrew Simpson, for example.

The vinyl writing on the walls of the exhibition is also part of an exhibit on new materials rights?

Yes, it’s vinyl made from algae, which can be produced in many colours. It is by a start-up called Other Matter by inventor Jessie French. Apart from using the vinyl for the exhibition text, we’ve also displayed them as large Pantone swatches because we wanted to make it very clear that it is a commercial product, not just research. It’s a great invention.

The object captions list not only designers but also collaborators such as scientists and ecologists, why was that decision made?

We wanted to be very clear that making good products is about collaboration. When you’re talking about material technology and production systems, the designer is only one part of it. In some cases, the designer isn’t even the instigator. We believe that every product is designed in some way, and designing is not an act that can only be done by designers – anybody can design.

What is an example of that in the exhibition?

Clean Grow is a good example, it was developed by Olsson’s, a Brisbane-based designer, alongside Sea Forest, a seaweed harvesting company, and scientist Rocky De Nys. The product is a salt lick for cattle and livestock. A salt lick is something used in modern farming of herd animals who need salt in their diet. They often derive salt from blocks that are provided in their fields, so it’s a kind of dietary supplement product. This salt lick is unique because it has a secret ingredient derived from seaweed, which reduces methane production in the gut of the animal, which is a huge contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, especially the farts of cattle. This reduces 98% of that methane product. That’s highly scalable and impactful.

Of course, there is the more subtle discussion that beef production includes other problems, so we still need to think about the industry as a whole and perhaps reduce the amount of beef we consume overall.

I like how invisible the problem being addressed is. One of my favourite objects in the exhibition is similarly subtle: the Australia Post envelopes. Could you speak about those?

Before this exhibition, I didn’t know about this design change, which is so interesting but pretty low-key. Basically, a woman called Rachael McPhail started sending more post during the COVID lockdowns. She realised it would be cool if you could list the traditional name of the Country that you live on, on your mail. So, she gathered 14,000 signatures to support a change in the design of post packs and envelopes and successfully lobbied Australia Post. They added a box and line on the envelopes that says “Traditional Place Name (if known)”. Alongside this, they also created a guide to all the different Countries of the First People of Australia, so you can look that information up, because lots of people might not know.

I love this project because it’s a really subtle thing – a small graphic design change – but normalising language and inviting people to become more familiar and comfortable with it can make significant, real changes.

Overall, the second section of the exhibition is more socially focused, is that correct?

Yes, these are examples of social design. So we’re thinking about the fact that we can redesign the rituals of life – that any moment of the day is a touch point where we can intervene and change things. We’re making it clear that we need to redesign some of our exclusionary rituals and behaviours.

The Equal Crossings project, for example, replaces the understood-form-of-a-man icon on the pedestrian traffic lights in Melbourne with the understood-form-of-a-woman. While it’s still quite binary, it begins to make you think about how and why things are designed and who they are designed for.

On the note of who things are designed for, how does the exhibition consider how to design for animals as well as humans?

We live amongst wildlife, but we don’t include them in our lives the way we could. One example of this in the exhibition is When Wildlife Moves In, led by designer Bethany Kiss. They’re presenting the concept that urban environments can be some of the richest and biodiverse environments in the world. We usually think of wilderness as being biodiverse but, in fact, there is a lot of food, water and accommodation available in urban environments for animals who want to move into that.

Their project gives advice on how to build homes that are more welcoming of animals, is this something you’re seeing more people in design and architecture think about?

I think this understanding of the more-than-human world and our relationship to birds, insects, plants and animals are shifting. It’s interesting to think: how does this shift then feed into new architectural typologies? New design strategies for landscape? Other things?

Another example is the Bandicoot Crossings Paw Bridge by Monash Urban Lab, which is a project that’s already out there in landscapes, helping animals to move and live on land that humans have changed.

I like how low-tech or undesigned it looks, it’s just a series of plastic pipes strung together over a stream to make a mini-bridge.

Yes, it does the job, and it doesn’t need to be complicated. We’re showing that someone has taken the care to think about how a bandicoot would get across human-made waterways. The bandicoot predates humans’ farming of the land. Someone’s thought: What can we do to increase the quality of life of these little creatures? So, it’s kind of a social design project as well.

So it’s about acknowledging that many people or organisms are using a single environment and thinking about how they can co-exist there?

Yes, in a similar but also quite different vein, we’ve got a project by Sibling Architecture called Deep Calm. It’s a tactile carpet and couch that hugs you, which are basically sensory aids for people who might be over stimulated, people who maybe have neurodiversity. What Sibling is getting at is that we now understand that neurodiversity is all around us. Some people are under-stimulated. Some people are overstimulated. Some people have anxiety.

Throughout the bulk of the 20th century, our educational, health and work environments have been designed around the concept that everybody is the same, which is kind of weird to think about now. We thought that students should all behave the same and have the same mannerisms, which is obviously just not the case at all.

That seems to relate back to what you mentioned at the beginning about the hidden consequences of design and how it can exclude people…

Yes, We’re only just beginning to understand that adjusting space, adjusting architecture, adjusting clothing and adjusting other things around us really does benefit people and increases their capacity to be fully functioning and contributing members of the community. I think we probably will see a lot more of this design in the coming decades, maybe it will be more common in people’s homes, and certainly in workplaces. Imagine if every workplace had a sensory area where you could go for a low-stimulation 15 minutes…

The exhibition ends with a series of new construction materials – from glass bricks made from recycled analogue TVs to bench tops made with recycled solar panels – do you have a favourite material in this section that you hope will be scaled up?

A lot of the final section deals with construction materials that reuse existing waste – this looks at materials having an impact in the shorter term. However, I think that some of the other examples which are more circular, naturally-derived and plant-based, like the hemp-based insulation and building material, HemPanel, are really important for the longer picture.

Photography

Eugene Hyland

Lisa Cohen

Sean Fennessy

Mark Lilly

Grant Hancock

Christine Francis

INDESIGN is on instagram

Follow @indesignlive

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

At the Munarra Centre for Regional Excellence on Yorta Yorta Country in Victoria, ARM Architecture and Milliken use PrintWorks™ technology to translate First Nations narratives into a layered, community-led floorscape.

For a closer look behind the creative process, watch this video interview with Sebastian Nash, where he explores the making of King Living’s textile range – from fibre choices to design intent.

From radical material reuse to office-to-school transformations, these five projects show how circular thinking is reshaping architecture, interiors and community spaces.

Milliken’s ‘Reconciliation Through Design’ initiative is amplifying the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists, showcasing how cultural collaboration can reshape the design narrative in commercial interiors.

Designed by Woods Bagot, the new fit-out of a major resources company transforms 40,000-square-metres across 19 levels into interconnected villages that celebrate Western Australia’s diverse terrain.

In an industry where design intent is often diluted by value management and procurement pressures, Klaro Industrial Design positions manufacturing as a creative ally – allowing commercial interior designers to deliver unique pieces aligned to the project’s original vision.

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

True sustainability doesn’t have to be complicated. As Wilkhahn demonstrate with their newest commercial furniture range.

A calm, gallery-like boutique by Brahman Perera for One Point Seven Four brings contemporary luxury and craft to Strand Arcade.