A recent exhibition at the Robin Boyd Foundation in Melbourne invited visitors to think deeply about sheds and what this under-appreciated building typology can teach us about construction and living today.

September 16th, 2025

Sheds are deeply personal places. They might be used to store your gardening and DIY equipment or as an artist studio, granny flat or study. Usually situated in a garden, they are places associated with solitude, usefulness, respite in nature and leisure activities. Despite their significance in many people’s lives, sheds are little discussed in architectural discourse.

A new exhibition, KOYA: shed architecture, at the Robin Boyd Foundation, recently sought to remedy this oversight. “Architecture often carries an unconscious hierarchy, where large projects are seen as more prestigious, while smaller ones, which lack monumentality, are not as valued,” explains the curatorial team, comprising Japanese architects Mio Tsuneyama and Fuminori Nousaku and Nancy Ji, a designer, architect and lecturer. “We have much to learn from sheds,” they say.

The exhibition’s premise is that studying shed design can offer lessons in how to be resourceful of materials, sensitive to local contexts and embrace modest scales of construction that are less environmentally damaging. “The shed typology experiments with minimal spatial requirements, prompting us to question how much space we really need,” say the curators.

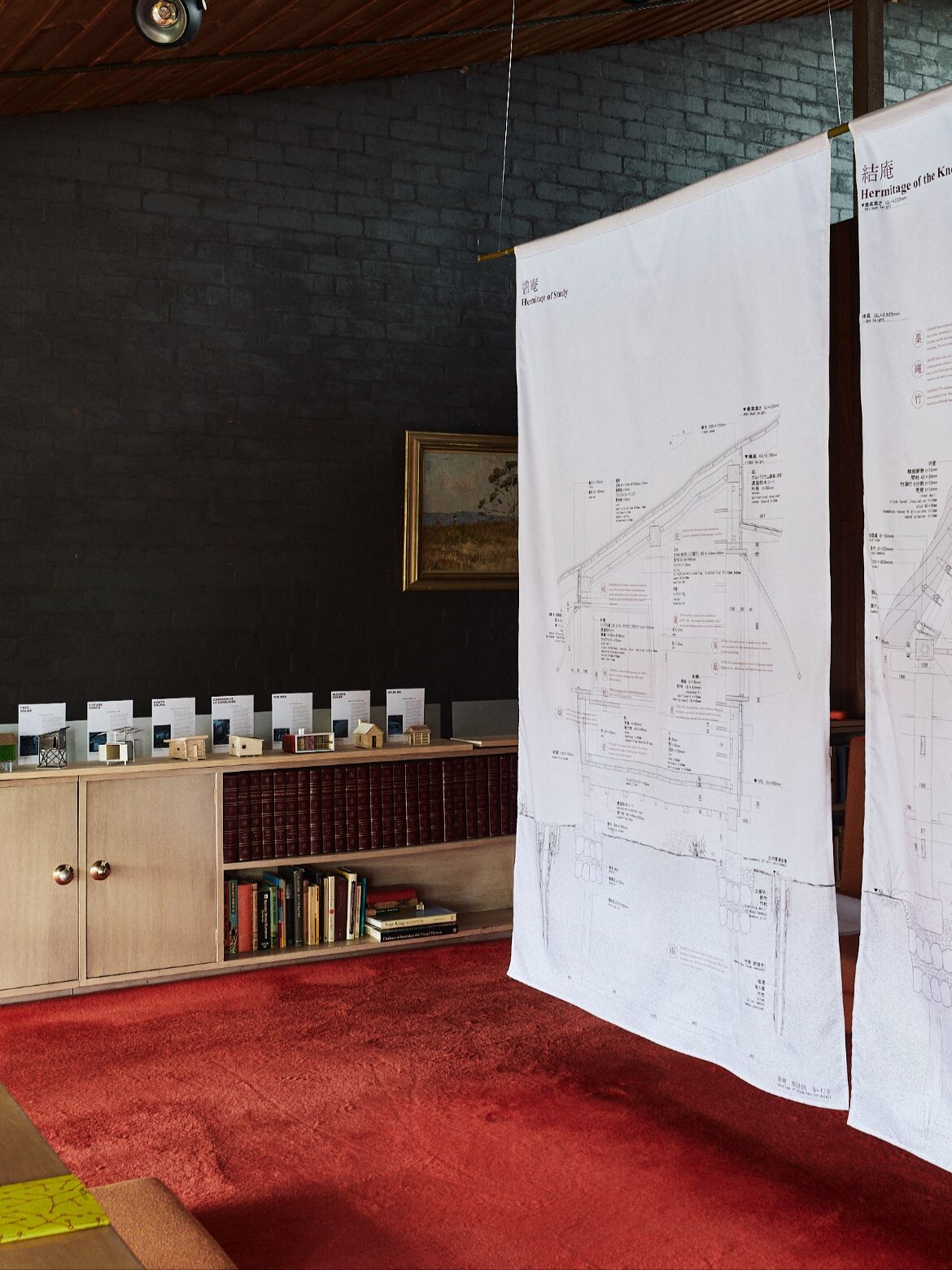

To tangibly communicate these ideas, a series of models were used to chronologically trace notable sheds throughout history – their 1:50 scale pleasingly fitting with the subject matter of the exhibition. These 16 models were made by students of Ji’s Master of Architecture studio, Vernacular Spectacular: Ecologies for Living at the University of Melbourne.

The historical investigation begins in 1211 with a model of the house of Japanese poet Kame-no-Chomei and ends in 2021, with Gerald Dombroski’s Picalo Cabin, which used only materials salvaged from the New Zealand property where it is situated. “We selected projects not according to who built or designed them, but for their ideas and construction, aiming to show a range of techniques across different contexts and time periods,” explain the curators.

Other highlights included a green shed with a structurally interesting and characterful cross-brace by Lina Bo Bardi Studio; The Box by Ralph Erskine which works hard as a living space, cleverly squeezing a kitchen, fireplace, terrace and hanging bedroom into its compressed area; and Arata Isozaki’s Tree House, built by the well-known Japanese architect for himself as a summer retreat in 1982. The latter is notable for its staircase that is carved from a single tree.

In another area of the exhibition sat six additional 1:50 models that travelled to Melbourne in Tsuneyama and Nousaku’s suitcases. These represented experimental shed projects made by the Japanese duo over their career. Their Humble Room for One (2021), for example, was displayed through two models – one showing its timber beam structure, the other an exploded model with its roof suspended, allowing visitors to peer into its interior and understand its liveability and materiality. Ji describes this project as “a playful take on the minimal dwelling which also considers the whole life cycle of materials, energy and waste.”

Other projects included a stone and timber sauna overlooking Mount Fuji, constructed using regional craft techniques; a solar-powered remote work cabin; and a tiny thatched house in rural Chiba created in collaboration with local carpenters.

Related: The inaugural Murcutt Pin goes to Francis Kéré

Alongside Tsuneyama and Nousaku’s tiny models are large-scale drawings of the cross-sections of their projects, charmingly annotated with information about materials, construction methods, energy cycles, soil information, foundation details, contextual information and visuals of how people occupy the space.

Overall, the exhibition offered a glimpse into Tsuneyama and Nousaku’s long fascination with shed architecture, or koya. “In Japanese, ko means ‘small’ and ya has several meanings, most commonly, the ‘ya’ is used to indicate a type of shop or store, such as panya (bakery) or honya (bookshop),” they explain of the title. This reveals how shed like-architecture has nuances in understanding and uses across cultures.

While the exhibition only ran for four days (September 4th – 7th), the curators hope that the display, talk programme and their work with students on this subject will have a longer impact encouraging people to live in closer relationship to the environment through small-scale architecture.

“We hope visitors can appreciate the joy that well-considered smaller projects can have,” says Ji. “Sheds enable garden cultures, DIY practices, native ecologies – and can even add more density and diversity in our neighbourhoods as we search for new ways of growing, making, sharing and living.”

Robin Boyd Foundation

robinboyd.org.au

Photography

Michael Pham, courtesy of the Robin Boyd Foundation

INDESIGN is on instagram

Follow @indesignlive

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

Welcomed to the Australian design scene in 2024, Kokuyo is set to redefine collaboration, bringing its unique blend of colour and function to individuals and corporations, designed to be used Any Way!

A curated exhibition in Frederiksstaden captures the spirit of Australian design

The new range features slabs with warm, earthy palettes that lend a sense of organic luxury to every space.

For Aidan Mawhinney, the secret ingredient to Living Edge’s success “comes down to people, product and place.” As the brand celebrates a significant 25-year milestone, it’s that commitment to authentic, sustainable design – and the people behind it all – that continues to anchor its legacy.

A multi-million dollar revitalisation of the heritage-listed venue at Brisbane’s beauty spot has been completed with The Summit Restaurant.

The winners of two major Powerhouse design initiatives – the Holdmark Innovation Award and the Carl Nielsen Design Accelerator – have been announced with the launch of Sydney Design Week 2025.

Piers Taylor joins Timothy Alouani-Roby at The Commons to discuss overlaps with Glenn Murcutt and Francis Kéré, his renowned ‘Studio in the Woods,’ and the sheer desire to make things with whatever might be at hand.

On 6th September 2025, Saturday Indesign went out with a bang at The Albion Rooftop in Melbourne. Sponsored by ABI Interiors, Woodcut and Signorino, the Afterparty was the perfect finale to a day of design, connection and creativity.

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

A multi-million dollar revitalisation of the heritage-listed venue at Brisbane’s beauty spot has been completed with The Summit Restaurant.

With the 2025 INDE.Awards now over, it’s time to take a breath before it all begins again in early December. However, integral to the awards this year and every year is the jury – and what an amazing group came together in 2025.