Respected nationally and internationally, Susan Cohn merges art, craft and design. She designs for Alessi, creates commission work and delights in the expression of street-culture and its interplay with technology. Yet she enjoys the long traditions of gold- and silversmithing, is inspired by the rituals and connections of everyday life and proudly calls herself a craftsperson. Where is Susan Cohn coming from?

July 16th, 2014

Susan Cohn’s basement studio in inner-city Melbourne is home to the practice she began in 1980. It’s the production house, operating theatre, nerve centre and persuasion room, and every item – machine, tool, material, furnishing, reference, keepsake, gizmo or shred, necessary or not for the translation of her ideas into three-dimensional form – has its place.

Being organised, she says, is part and parcel of being a jeweller. You can add the focus and determination, not only to make it work, but to make the whole business work for her. Mix that with a sharp eye, pragmatism, patience for precision and an abiding curiosity. “It’s always the whys,” she says. Her hearty ebullience delivers intellectual substance and a provocative turn delivered with wit. She has an absolute resolve to live a creative life to the full.

From Graphics to Jewellery When, as a nineteen-year old single mother in the 1970s, Cohn approached Garry Emery looking for work, the black-clad cardinal of graphic design in this country became Cohn’s mentor. Emery introduced her to graphic design, art and Modernism in particular. “It was the best training I could ever wish for,” says Cohn who, along with a graphic language, developed an understanding of research and problem-solving, learnt how to write her own brief, deal with clients and manage a business. It was also at this time that she met her partner, architect John Denton, a client of Emery’s.

Cohn left Emery less than five years later. But the experience was formative and graphics remain integral to her practice. Platonic form, geometry, colour, typographical detail, wit, spatial understanding and a concern with the multi-layers of information – Emery can still see these elements in her work. As Cohn remarks, “You don’t go through that sort of training with Garry and not have that implanted in you!”

But disenchanted with the advertising world, a suggestion at a dinner party led Cohn to study gold- and silver-smithing at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT). “I fell in love instantly – with the smell, the physicality, the planning and the making. In comparison to graphics where decisions are dictated by so many different people and emotions and egos, it was a delight to be able to conceive of something, make a model, make the real thing and control the whole process. And that was as exciting as exploring materials – each material has its own language – just playing with them to see what they could do. I was just fascinated with it. I still am. It’s my life.”

The Practice of Craft “It’s so hard when you come out of art school to set yourself up and keep going.” But in 1980, in anticipation of her graduation, Cohn approached Harry Rowlands (the RMIT technician who had been invaluable in teaching her tool-making) and lecturer, Marian Hosking, and a plan was hatched to create an access workshop where participants (mostly other recent graduates) could rent space and share overheads and equipment. The trio formed a partnership and, with support from the Australia Council, Workshop 3000 was established. “There were five of us in the beginning, it was a very vibrant atmosphere. We went in every competition we could find.” Initially they held group shows and began to attract attention. Cohn took over as sole director in 1984 and continues to take in graduates to pass on her experience and to help them get established.

Workshop 3000 remains a workshop in the true sense of the word, in that it is not only where the work is made, but also where it is sold. Fifty percent of Cohn’s output is commission work, so clients come to the studio to formulate a brief, and discuss models for jewellery and tableware. “I do a lot of relationship rings, which is cream. It’s beautiful work because I always have to get to know the people to think of something [appropriate] to make for them, and you develop this connection.”

Principles of Production Production work, though, is the mainstay of the studio and another decision taken around 1980 has been critical to Cohn’s career. “I wanted to make a living out of [doing] what I loved,” she says, which meant keeping production costs down while maintaining design integrity. “Making inexpensive beautiful things is much harder than to do one-off art pieces. I wanted to take up that challenge. ”She focused on creating semi-mass produced objects which could be individualised in the finishing. Working in series, she developed a number of press-tooled aluminium forms, and with her doughnut bracelets in particular, she felt she had “started to crack the simplicity [required].” The aluminium is diversely coloured and joining and finishing the pressed forms allows ample opportunity for customisation. In 1984 she held her first solo show, which included her well-known interchangeable disc earrings along with the doughnut bracelets. These items, through continual evolution, remain the basis of her production work today.

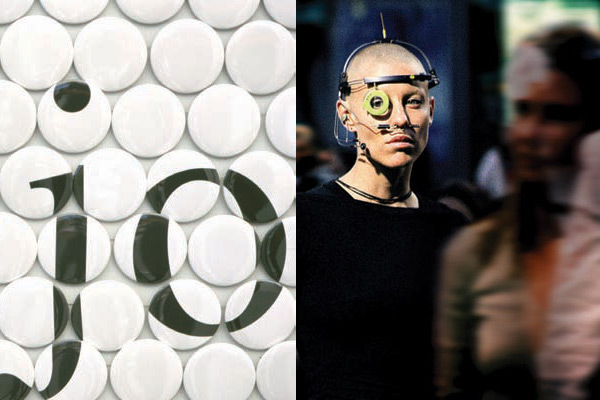

(Left) Craft is a Hand Job (detail) (Right) Hubhead Photo

In 1988 Cohn won the National Craft Award, which she says, “really kicked my career along. Melbourne gallery director, Anna Schwartz, approached me about exhibiting with her and that was a major breakthrough. It’s been a fantastic relationship,” says Cohn, who has shown at Anna Schwartz Gallery every couple of years since the first exhibition in 1989. As a result, art practice and exhibiting has become integral to her work. Cohn has always valued incisive discussion of her ideas with friends and colleagues: John Denton, Garry Emery, Sue Rowley and others. “Anna Schwartz is another one I’ve had quite in-depth conversations with about work, because initially she called me a sculptor and I said, no, I’m a jeweller. I’m a craftsperson. You call me a sculptor and you take my power away because my language is craft not sculpture. She agrees with me now, but it took a while. She also always gives me the freedom to do what I want to do.”

Railing against the standard notion of the jewellery exhibition – the ‘craft show’ in which everything the jeweller has made is on untouchable display – Cohn “wanted to talk about jewellery in a different way,” to explore the typology of jewellery itself, and the different terms on which it is valued. “The exhibition is a chance to play – with whatever I’m thinking about, or angry about, or observing or responding to. Different pieces start out or end up in exhibition, or out of exhibitions there’s always new production work. One feeds the other all the time.”

Inspiration and Exhibitions From the start, many of Cohn’s ideas sprang from street culture. She mentions the launch of the Walkman in Hong Kong: “It was as if everybody was suddenly wearing orange earrings. I started to notice how something small and unobtrusive on the body was becoming decoration – lapel microphones for instance.” Out of this grew a fascination for sub-cultures, how they use style to express identity, and how jewellery and objects that function like jewellery operate as coding, often secret, to indicate membership of social groupings. That interest has since spread to technological and medical applications, bionic ears, prosthetics for instance, and where jewellery might intersect with this expanding field. In every case, the motivation is an intense curiosity about people: behaviour and rituals, meaning and significance. “I’ve become a very practised voyeur.”

Halo, scratched and painted aluminium neckring

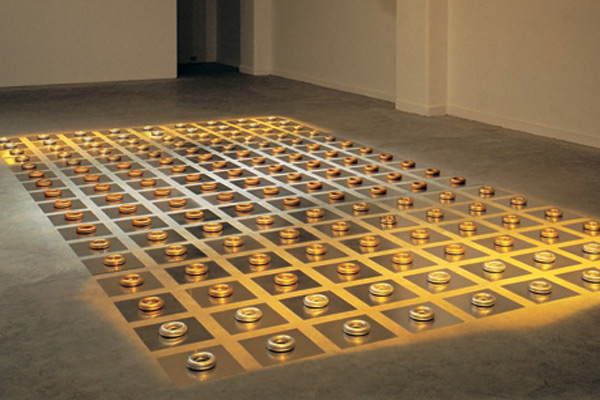

In the 1989 exhibition, And does it work?, Cohn investigated the useful everyday objects people carry on their bodies – security passes, key rings, cellular phones and headphones. Stripping them of their functionality, she transformed them into objects used purely for adornment. In Way Past Real, in 1994, 153 apparently identical gold doughnut bracelets were displayed in four groups. In one assemblage a single pure gold bracelet had infiltrated the array of plated ones. In another group of gold anodised bracelets, only one ‘original’ was made by Cohn. The third set looked like gold, but was in fact cunningly lit aluminium, and the fourth group of all gold bracelets confounded expectations of what gold should look like. In her luxe-minimalist style Cohn was raising questions about authenticity – the real, the original and the fake – and about value as a construct that goes way beyond materiality to include personal, emotional and social signifiers.

This exploration of value can also be seen in her compressed brooches, which developed from the idea of the compaction machines used to reduce cars to scrap. They evolved, however, to include fragments of gold and silver jewellery, items past their wear-by-date, which add a layer of memory or personal significance to each piece. Later she developed her Sheath Rings, in which silver or gold is hidden inside a sleeve of aluminium that disintegrates with day-to-day wear revealing the precious metal inside. In this way abstract notions of time and personal interaction become as much part of the pieces as gemstones are in traditional jewellery. Once again, Cohn is addressing value, creating it out of personal significance rather than material worth.

In the 1992 exhibition, Cosmetic Manipulations, Cohn comments, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, on the cult of youth, showing a series of finely constructed pieces designed to hold and highlight the wrinkles and folds of sagging skin, the defects of age. Reflections on a Safe Future, in 1995, presents a series of dragonfly talismans designed to hold condoms. The wings are the wrap-around lenses of Oakley sunglasses, but metamorphosis has occurred, and like the option to choose safe sex over unprotected, change is required. Here Cohn is concerned with direct social message. She follows up, in 1999, with Survival Habits, which comments ironically on the kind of future that is fast approaching and what we might need to face it – a tiny brain jack, for instance, so we can interface directly with any computer; a phial of personal memory perfume, which transports us back to a person, place or time of our choice; a miniature gold hearing device, since telephones will be redundant; and a cure-all drug that can only be used once – all packed into a Cohndom box.

Gibsonia #5, insect pendant with condom box

Designing for Alessi Light, portable, non-gender specific, suitable for machine vending, and made in different materials, the Cohndom Box, which first surfaced in the Reflections exhibition, was the second Cohn design to be taken up and mass-produced by Alessi. The first, the Cohncave bowl, has been produced since 1992 after Cohn had been one of 140 designers invited to enter an international competition (Alberto Alessi, keen to broaden his then all-male stable of designers, had only invited women to enter). Made from two sheets of pressed, perforated aluminium simply joined at the rim, the Cohncave satisfied Cohn’s criteria that production objects be functional, beautiful, accessibly priced and individual. The moiré pattern created by random placement of the two layers of perforated aluminium, makes each mass-produced bowl an individual item. As for the association with Alessi, she says, “I’ve had a fantastic relationship with them and I think the experience has fed both ways. They hadn’t worked with a craftsperson at that time, (1990).” In fact Alessi’s product development technician, taking Cohn on a tour of the factory while the Cohncave was being made, began to explain the manufacturing process to her. Alberto Alessi quickly set the record straight.

Recognition In working successfully across the boundaries between craft, art and design in this country, and having achieved international renown, Cohn’s career has been unique. In recognition of this, the National Gallery of Australia mounted its first ever survey exhibition of a contemporary jeweller and metalworker. In 2000, Techno Craft: the work of Susan Cohn 1980 to 2000 was launched in Canberra before travelling to six state venues.

Cohn’s work is also held in virtually all major state galleries along with the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Royal College of Art, London, the National Museum of Scotland, and the Alessi Museum, Cruisinallo. Apart from solo and group shows around Australia, she has also exhibited in Tokyo, London, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Amsterdam, Munich, Singapore, Shanghai, Taipei and Dunedin. While Cohn enjoys the measure of this success, she remains focused on work yet to be done.

Craft and Writing Cohn sees herself perpetuating the long tradition of craft, which is based in the personal creation of functional and beautiful everyday objects. “That’s what attracted me to it in the first place. The language of craft is one of people and rituals. I’m adamant about craft because it suffers from an inferiority complex and I think it has an enormous amount to offer.”

Way Past Real, Exhibition Installation

Moreover, craft theory has been largely overlooked. Thinking about craft as a maker, Cohn realised, is quite different from researching and writing about craft and craft theory. Fascinated by the questions it raises, she decided in the 1990s to integrate writing into her practice. After discussions with Professor Sue Rowley, now Pro-Vice Chancellor at the University of Technology, Sydney, Cohn embarked on a doctoral thesis focused around managed identity and jewellery as a cultural signifier. Her 2003 exhibition, Black Intentions, was “essentially a work about personal identity and value, community and the relation of the individual to a cultural group, family or lifestyle.”

As the thesis nears completion, she is more fired up than ever about the value of craft and the necessity of raising discussion about it. In her 2004 exhibition at Anna Schwartz Gallery and at The Depot Gallery, Sydney, entitled 1 Protest/1 Object Cohn showed a series of large pieces compiled from badges. 1 Protest dealt with war, whilst in 1 Object the badges, in various conformations, simply announced, in hand-written script ‘Craft is a hand job’. Cohn was thrilled that the extra badges she’d made as hand-outs were snapped up and worn by the art afficionados present. The provocateur was enjoying her work. But is this her last word on craft? Not on your life.

Portrait by Anthony Browell.

Susan Cohn was originally featured as a Luminary in Indesign issue #22.

INDESIGN is on instagram

Follow @indesignlive

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

At the Munarra Centre for Regional Excellence on Yorta Yorta Country in Victoria, ARM Architecture and Milliken use PrintWorks™ technology to translate First Nations narratives into a layered, community-led floorscape.

For a closer look behind the creative process, watch this video interview with Sebastian Nash, where he explores the making of King Living’s textile range – from fibre choices to design intent.

Congratulations to Kerstin Thompson, 2023 recipient of the Australian Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal. We revisit Kerstin’s many accomplishments, among them being named an INDESIGN Luminary.

As NGV’s top design curators, Simone LeAmon and Ewan McEoin have big dreams for the design sector. And they’re coming at it with energy and ambition.

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

At Kilvington Grammar, ClarkeHopkinsClarke Architects (CHC) has converted an old single-storey library into three levels of flexible, collaborative learning spaces.

As Roberto Palomba visits Australia, Space Furniture unveils a 450-square-metre apartment installation that positions Kartell not as a collection of objects, but as a complete way of living.