The extraordinary French architect, Manuelle Gautrand, has recently completed PHIVE, a major civic project in Paramatta, NSW. We took the opportunity to talk with her about architecture.

February 17th, 2026

What are the main turning points in your life that led you to architecture?

Ever since I was a child, I’ve been strongly attracted to art and I’ve always believed that architecture has a profoundly artistic dimension. Architecture is not only created to provide shelter, it must also give emotion.

Our famous French writer Victor Hugo wrote, “The cities of humans need monuments, otherwise where would be the difference between the city and the anthill?” Architecture must give meaning to a place and leave a trace in our memories.

I’ve also always been greatly influenced by my travels, from a very early age. These trips taught me to look, to question, to put my prejudgments aside to better understand the places in which I found myself. It’s important to cultivate great curiosity and to discover other attitudes, other cultures, other ways of living on earth. Travel makes you humble in a way.

I believe you spent time in Australia prior to this project?

When I was 20, I went to Australia and it was a real shock: I was leaving Europe for the first time, and I discovered the grandiose scale of the landscapes, the immensity (for me at the time) of Sydney Harbour and the vastness of the city. Europe is a “garden”, the landscapes are rarely wild and their scale remains a European scale: nature punctuated by the traces of man, villages, dwellings and crops everywhere. Man has been everywhere!

In Sydney Harbour, I discovered Jørn Utzon’s Opera House, and this is certainly part of what made me want to become an architect. I was so touched by its beauty, its successful insertion into the harbour, its grandiose scale on the equally grandiose scale of the harbour.

As an architect, I wanted to keep this emotion in my memory and keep reminding myself that the most successful architecture is the one that is able to celebrate a site.

Related: Design stewardship with John Walsh

There is a lively quality to your work that is poetic, origami-like and with a sense of adventure. Can you talk to the way you bring unexpected qualities to your work?

My projects are different from one to another, precisely because each one tries to celebrate the site in which it comes to ‘make its own nest’. Here again, we must be humble: building a project on a site requires first of all understanding the site, listening to it, detecting its qualities in depth, its history, its geography, its climate and light and what happened there before you arrived. The notion of context is fundamental: a project must first and foremost be contextual and this is the starting point for it to be ecological; building requires delicacy and a form of empathy with the site you’re going to occupy. And this doesn’t prevent you from creating a strong, powerful architecture that leaves its mark on your memory.

Light and colour are also important in your work?

I was born in Marseille and I can truly say that the light, so special around the Mediterranean, often so harsh and strong, cutting such graphic shadows and enhancing all colours, left its marks on my childhood. For me, working with light is fundamental: architecture changes and evolves with the hours, the weather and the month of the year, and in a way, it is light that brings our built works to life. Architecture becomes mobile and changeable with light, metamorphosing with it.

There is a Frenchness that makes your work sexy and exciting, never boring, always assured. Can you talk to how being French makes itself felt in your work?

I think perhaps we have a very urban culture and we are accustomed to a pile of histories that form the very richness of any site. As a Frenchwoman, I also have a love for public space, which for me is sacred. It is the binding force of a community, the cement of a society. Each of my projects seeks to open up to the public space, whatever it may be, and to maintain a strong relationship with it. Architecture must be no more than a filter between public and private, letting flows pass through and knowing how to remain porous in some way.

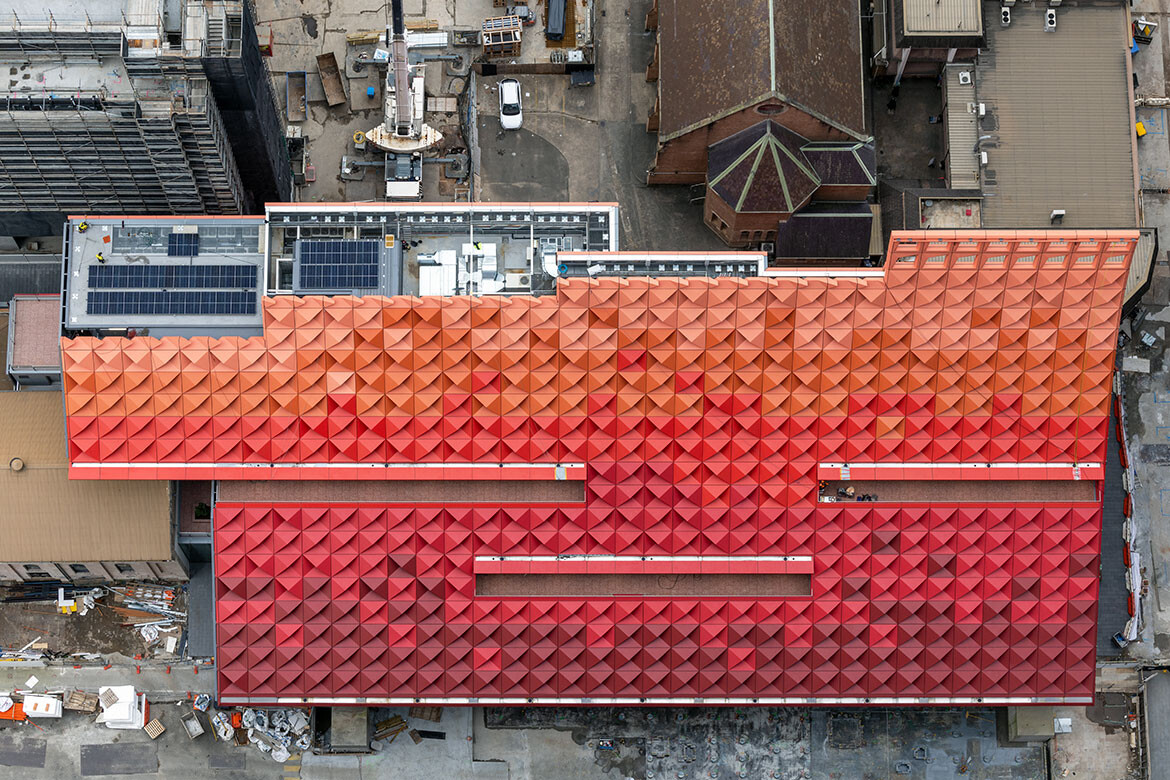

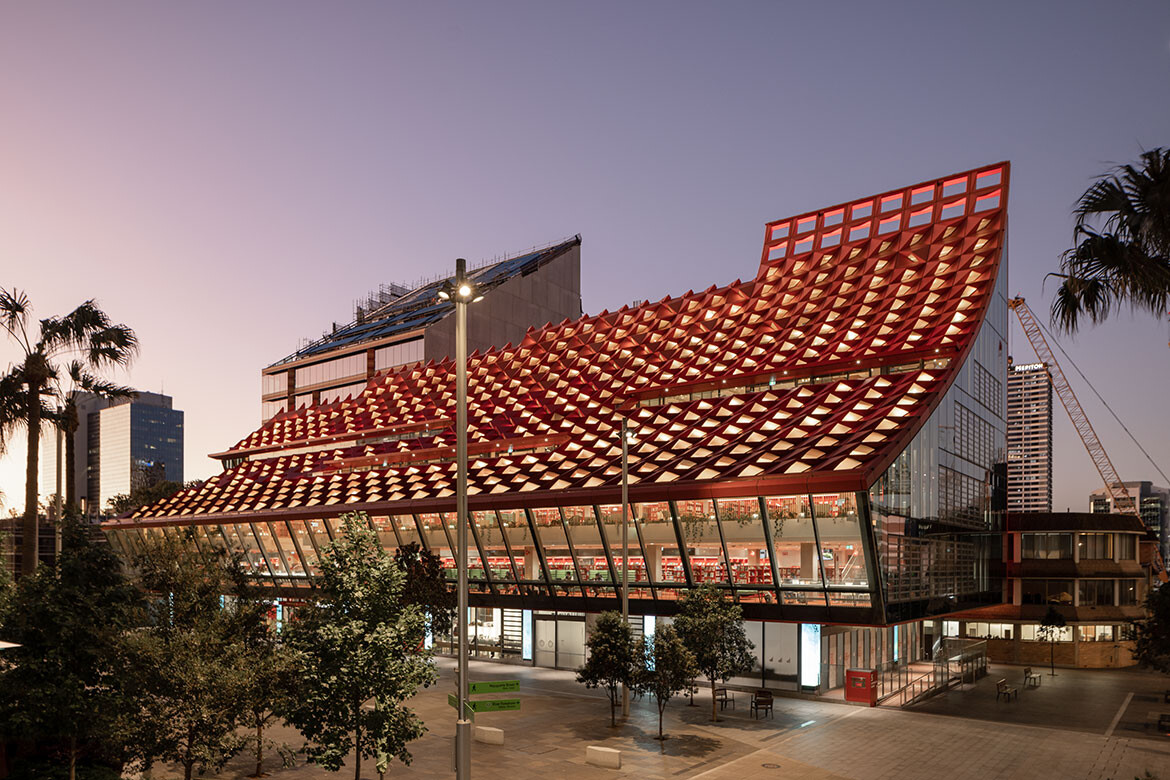

How, then, has your architectural style been explored in PHIVE?

Our cultural centre in Parramatta was really designed to highlight the square that adjoined the site to the south, and make it a truly central square, both for the project and for the neighbourhood as a whole. The way in which the project’s volume is sculpted so that it casts no shadow over the square, whatever the time of year, is a form of politeness that is dear to me.

And this sculpted volume offers multiple qualities. It allows us to create successive levels, each offering a direct view of the square. They are like balconies, installed one above the other, tumbling down towards the square. The square becomes the stage for the theatre we create: the square and the building form an indissociable whole, one enhancing the other and vice versa.

In this way, all our projects seek to establish this link with the public space and try to ensure that both the public space and the building emerge even stronger after our intervention.

Were you able to push the project as far as you wanted? Tell me about the need for colour in an otherwise serious building.

Everything about the Parramatta project celebrates the need for a cultural project in a city. PHIVE is a public, cultural and festive space, which through its spatial organisation, its openness to public space, its programmatic generosity, its aesthetic strength, honours the feeling of community, the pleasure of sharing a moment in this multi-faceted place. Its unexpected shape, sculpted by the path of the sun, and its powerful colours are there to make it a magnet, the emblem of the neighbourhood that you can’t pass by without seeing.

Yes, colour is important, of course: it’s part of a strategic process aimed at enhancing this public facility. The neighbourhood is full of glass buildings with grey curtain walls and ultimately quite corporate. We wanted to break away from this monotony by creating an unexpected “object”, at once very respectful of this urban context, but at the same time highly unique, powerful and artistic.

Manuelle Gautrand

manuelle-gautrand.com

Photography

Sara Vita

Luc Boegly

Brett Boardman

INDESIGN is on instagram

Follow @indesignlive

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

In a tightly held heritage pocket of Woollahra, a reworked Neo-Georgian house reveals the power of restraint. Designed by Tobias Partners, this compact home demonstrates how a reduced material palette, thoughtful appliance selection and enduring craftsmanship can create a space designed for generations to come.

Sydney’s newest design concept store, HOW WE LIVE, explores the overlap between home and workplace – with a Surry Hills pop-up from Friday 28th November.

Following his appointment as Principal at Plus Studio’s Sydney office, architect John Walsh speaks with us about design culture, integrated typologies and why stretching the brief is often where the most meaningful outcomes emerge.

Hammond Studio has completed its own workplace in Sydney, placing great emphasis on collaborative technology, light and of course high-quality detailing.

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

Returning to the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre this February, Melbourne Art Fair 2026 introduces FUTUREOBJEKT and its first-ever Design Commission, signalling a growing focus on collectible design, crafted objects and cross-disciplinary practice.

Jasper Sundh of Hästens shares insights on global growth, wellness-led design and expanding the premium sleep brand in Australia.