From third spaces to connections with the urban realm, Alison Huynh shares her vision for healthy hospital design.

September 15th, 2023

This comment piece by Bates Smart associate director, Alison Huynh, originally appeared in INDESIGN #87, the Health & Wellbeing issue. Find out more about the magazine and subscribe here.

Healthcare facilities are places in which we must muster all our physical, mental and emotional strengths, despite great odds. Patients are nervous, weak and in pain. Families and carers are worried, emotional. Staff are highly focused, stressed and time-poor.

We know that the hospital setting can impact experiences of all these end-users; this is a reality of hospital design that is widely accepted by designers, researchers and healthcare providers and administrators. We’ve been successful in creating smaller wellness-focused environments – internal spaces, like patient rooms, which we can make feel friendly and like home – but we have always struggled with the aspect of scaling up wellness to larger settings.

The end result is the hospital remains as a ‘sick place’, one that is intimidating, disorientating and foreign. Hospital environments work against creating experiences for people that help them to feel better.

In the design of major hospital projects, the experiential aspect of patient care is often subverted by the complex and technical nature of the facilities, where spatial planning and design are driven by practical functions and needs. These include stringent infection control, substantial and complex medical equipment, demands of observation and nursing, and the sheer number of specialisms, departments and beds required to meet their patient loads.

Many designers working across large-scale healthcare projects are coming to the realisation that their trusted design moves in fostering ‘wellness’ lose impact as they are scaled up. In trying to shift the perception of healthcare design and its value, boutique human-scaled projects are most effective. When applied en masse, however, a soothing pattern or rhythm can become repetitive and monotonous, or premium fit-out products are substituted for cheaper, lower quality ones.

To recalibrate, hospital design must incorporate the macro scale tools of city-making, in addition to the tools of making small and intimate spaces. A legible environment within the vast scale of a health campus needs to be memorable to a wide variety of people in different states and at different times. This is more akin to the temporal construction of a city, which we only experience in small fragments, and over long periods in time.

In addition, we look increasingly to our cities for welcoming ‘third spaces’ – places that belong to everyone, supporting a neutral ground for exchange and engagement.

In the city, health services integrated with third spaces would bolster confidence in patients and their families to feel in control of their health and promote early and active engagement with preventative healthcare.

We can shift towards making this kind of multi-layered environment in the hospital by weaving internal and external places into shared public realm. While a hospital must be a controlled and weather-protected environment in many (but not all) cases, connecting inside and outside of the hospital to the broader urban realm can assist in creating comprehensible and memorable connections.

This requires early commitment to collaboration and cross-fertilisation. All different types of design experts, from clinical planners to design architects and interior and landscape designers, need to be involved in placemaking. Taking its cues from the city, the hospital must work with movement, topography, and a wide range of clinical flows. By working together, we can do more to create coherent multi-layered spaces that bring together these complex factors to create paths and nodes that connect journeys not only with the hospital front door, but also the multiple distinct health services and places within.

Ultimately, we will all need to interact with the hospital in our lifetimes. Its built environment is constantly changing, growing and adapting, just like the urban fabric. The cumulative effects of thoughtful and site-specific placemaking can pivot the hospital away from its image as a sick place and help it become one that, at its largest scale, better supports good health experiences and wellbeing.

Find out more about INDESIGN #87, the Health & Wellbeing issue, here.

Bates Smart

batessmart.com

We think you might also like this comment piece on aged care by Fender Katsalidis’ Jessica Lee.

INDESIGN is on instagram

Follow @indesignlive

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

In an industry where design intent is often diluted by value management and procurement pressures, Klaro Industrial Design positions manufacturing as a creative ally – allowing commercial interior designers to deliver unique pieces aligned to the project’s original vision.

Sydney’s newest design concept store, HOW WE LIVE, explores the overlap between home and workplace – with a Surry Hills pop-up from Friday 28th November.

At the Munarra Centre for Regional Excellence on Yorta Yorta Country in Victoria, ARM Architecture and Milliken use PrintWorks™ technology to translate First Nations narratives into a layered, community-led floorscape.

A contemporary rural home by Tomohiro Hata Architect & Associates reinterprets historic farmstead clusters in a bamboo-forest landscape.

Set among the rice fields near Shanghai’s Xinchang Ancient Town, The Catcher by TEAM_BLDG reworks two rural houses into a guesthouse that mediates quietly between architecture, landscape and time.

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

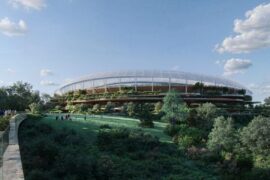

COX Architecture and Hassell have announced that they have been awarded the design contract for the new Brisbane Stadium.

DKO announces senior promotions across architecture, interiors and landscape, reinforcing leadership growth across Australia and Asia-Pacific.