If mindfulness is next to godliness, wellbeing is the holy grail. So how and why is design investing in the R&D of wellbeing?

It’s been sixty years since the World Health Organization first tabled the term ‘wellness’ as the optimal state of health of individuals or groups. Wellness, according to WHO, is a binary concept. Firstly, it requires “the realization of the fullest potential of an individual physically, psychologically, socially, spiritually and economically”. Secondly, “the fulfillment of one’s role expectations in the family, community, place of worship, workplace and other settings”.

Trouble is, we don’t always know what’s for our own good. That’s where the Well Living Lab comes in. Established in Rochester, Minnesota in 2015, the Lab was founded as a research centre to study the effect buildings – and the fittings and furnishings within – have on the health and wellbeing of humans.

“Because we spend over 90 percent of our time indoors, it is becoming exceedingly important to harness the built environment as a vehicle to support health and wellness,” says Dana Pillai, the Well Living Lab’s Executive Director. By making certain building and design decisions, we can change the culture of a space, and create a natural tendency towards health. For example, we can make staircases more accessible and inviting to passively encourage physical activity and the formation of healthy habits.”

All very well in theory, but the Lab is no mere think tank: it’s a practical design laboratory, 700 square-metres embedded with a dense network of sensors and smart building controls. A cloud-based infrastructure enables high fidelity replication of particular environmental conditions. “For example, we can mimic the quality of light from the sun on a sunny day versus the quality of light from the sun on a rainy day. We are also able both to reproduce the properties of daylight that are conducive to working and to reproduce the qualities of light that are conducive to sleeping and relaxation in the evening.” It’s like a NASA flight simulator for terrestrial builds.

“Through the Well Living Lab, we have a great degree of environmental control,” says Pillai. “Whereas in a typical workplace environment you may observe a certain change in behavior or biophysical response on a sunny day, for example, there are other environmental factors that might be at play. Because we can control environmental factors we such precision in the Lab, we can now better isolate variables, including light quality.” Pillai anticipates that the WELL Building Standard®, best-practice certification accorded by the International WELL Building Institute will soon become de rigueur.

Kellie Payne, Associate Director of Bates Smart is the author of a recent white paper entitled, Wellbeing in Design. Payne defines wellbeing as “a person’s individual ability to thrive in the workplace and in society as a whole” and points to the Wellbeing Index developed by the Australian Centre On Quality of Life at Deacon University as a guideline for architects and designers. Bates Smart applied many such principles to its fit out of the Salvation Army headquarters, in Redfern. Previously the homebase of the South Sydney Rabbitoh’s, the structure is divided into four floorplates over 11,213 square metres, with windows to the street at the front and a laneway at the rear. Incorporating office space for Army commanders and their staff, meeting and breakout rooms, a 400-person event space and a chapel, the interior needed to maximize a sense of comfort and respite, while simultaneously optimizing military efficiency. Uncluttered, it reflects a clarity of vision and quiet conviction that all shall be well.

Located on a busy arterial road, a high level of acoustic control was required to enhance that sense of being far from the maddening crowd. Perforated Tasmanian oak suspended below the air conduits absorbs noise and emphasizes the horizontal vastness of the space. A generous stair in an open well permits communication between floors, its landings doing double time as meeting places. On the other hand, privacy is readily available via a suite of hermetically sealed rooms. Furnished with elegant chairs and stools around generous work surfaces, the entire interior strikes the perfect work/life balance. Of note: all furniture and fittings, specified by Interior Design Project Leader Max Navius are well-priced original designs, proof that style can be attained on a budget. And that’s wellbeing for the design industry.

INDESIGN is on instagram

Follow @indesignlive

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

For a closer look behind the creative process, watch this video interview with Sebastian Nash, where he explores the making of King Living’s textile range – from fibre choices to design intent.

In an industry where design intent is often diluted by value management and procurement pressures, Klaro Industrial Design positions manufacturing as a creative ally – allowing commercial interior designers to deliver unique pieces aligned to the project’s original vision.

As PTID marks 30 years of practice, founder Cameron Harvey reflects on the people-first principles and adaptive thinking that continue to shape the studio’s work.

With its Academy report, WORKTECH sets out some predictions and reflections on the workplace in 2026.

Zenith introduces Kissen Create, a modular system of mobile walls designed to keep pace with the realities of contemporary work. The market is now defined by hybrid models, denser floorplates and the constantly shifting modes of collaboration – Kissen Create is a response to these shifting commercial needs. Ultimately, it solves an ever-present conundrum for […]

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

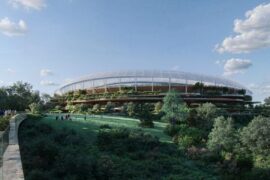

COX Architecture and Hassell have announced that they have been awarded the design contract for the new Brisbane Stadium.

Arranged with the assistance of Cult, Marie Kristine Schmidt joins Timothy Alouani-Roby at The Commons in Sydney.