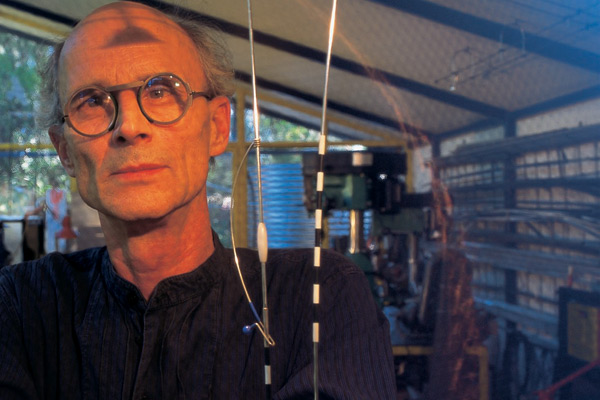

In the artfully designed modernist workshop in the back garden of his home in inner-suburban Adelaide, Frank Bauer – internationally recognised jeweller, industrial designer, light artist and kinetic sculptor – works in a colourful world all of his own making.

July 2nd, 2014

In a career spanning 35 years, Frank Bauer has designed and made jewellery, spectacles, a series of teapots, a range of lightweight furniture and prototypes for ingenious wind-driven sculptures.

His work has been exhibited in Europe and Australia, and is represented in major museums, including London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, the Bauhaus Archiv in Berlin, the National Gallery of Australia, the Galleries of Victoria, Western Australia and South Australia and the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney.

Bauer is exceptional, not just for the quality of his workmanship, but also for the breadth of his skills as a maker. “For me it’s not only sitting remote, drawing. Things happen much more once I get into the workshop and push myself. In the process of handling, touching and making I can experience things much better.”

Born in Hannover, Germany, in 1942, he grew up in a rich cultural environment during the period of post-War re-construction. His father, an architect, had trained at the Bauhaus. He had been taught by Kandinsky, and would often speak about Paul Klee, Ludwig Mies van de Rohe and other Bauhaus figures. The Dada artist, Kurt Schwitters, was a family friend. “I grew up with [my father] dragging me to the museums. And then I saw the Kandinskys, I saw the Kurt Schwitters, I saw Klees.” Exposure to these major artists on an everyday basis has left a legacy, as has his association with early modernist aesthetics and the art-meets-industry principles of the Bauhaus.

A varied education “Academia was a nightmare,” he says. “I kicked myself out of school.” At first he learned architectural drawing. Then, at 17, he began studying music – piano, cello, and for a time wanted to play jazz trombone before realising he had left it too late. Having always enjoyed working with his hands, “fiddling with train sets and radios”, at 20 he changed direction again. He learned welding and blacksmithing. Next he was apprenticed to two highly regarded German silversmiths, where he learned gold- and silversmithing, and enamelling. After further training in silversmithing in Ireland, he returned to Germany and studied industrial design and then architecture for several years. “I dabbled in this, dabbled in that – I always felt it was not good enough. My father was quite generous. He moaned and groaned, but he paid for the bills, paid for the study.” It took me a long time. I never had a definite career. I was always searching.”

In 1969, Bauer attended an exhibition of the work of Venezuelan artist, Jesus-Rafael Soto, a leading figure in the kinetic art movement, whose early explorations into the optical illusion of movement often used identical elements repetitively and moiré effects. “I loved that exhibition. All of a sudden this totally static [image] moves with your movement. It has another dimension, which the image itself doesn’t have – that was why I was always fascinated with kinetic [art].” Several of the themes Bauer has continually returned to over the ensuing years stemmed from this encounter – the repetition of forms, interactivity with the viewer or user, and real and illusory movement.

Innovative jewellery in Australia In 1970, Bauer worked as a model-maker at Frei Otto’s Institute of Light Space Construction. But having “met an Australian girl in Ireland”, he moved to Sydney, set up a jewellery studio and, as he says, “I fell on my feet.” His first exhibition was at the David Jones Gallery that same year and, while not one piece sold – he mentions an old Chinese saying that people buy with their ears – his career was underway. For this innovative jewellery, he had adopted a language of bolts and rods, screws and springs from the world of machinery. The very masculine designs often featured moveable parts to allow for adjustable sizing. While later work is cool and abstract, at this time it was much more expressive, almost impulsive.

An Australia Council Crafts Board Grant in 1975 prompted a re-location to the Jam Factory in Adelaide. In this period, Bauer was making rings and neckpieces exploring the kinetic and optical effects of reflections. The reflective surfaces were contained in small grid structures of gold or silver. However, these cubic constructions gradually became the sole subject of his designs.

A spectacular time in London In 1979 Bauer moved to London, where he joined the forefront of contemporary jewellery design. This was a vital and productive period for Bauer. He developed the cubic towers into ever more complex and intriguing pendants and made hinged and folding bracelets that played with notions of multiple configuration and interaction. He expanded his range of materials, from gold, silver and platinum to acrylics, stainless steel, titanium and aluminium. He produced working models for a range of counterbalanced mobile constructions, which would later become his wind sculptures. He was also lecturing on the BA course in jewellery, silversmithing and design at London’s Sir John Cass School of Art.

Of major significance at this time was his first encounter with low-voltage lighting. “Little tungsten halogen bulbs – so tiny and so bright – you see them everywhere now, but that was the beginning of it.” At a British Craft Centre exhibition in 1979 he saw the work of industrial designer, Ralph Ball, who Bauer regards as the originator of the low-voltage revolution. “I like to credit him because I thought the essence of [what he did] was just amazing.”

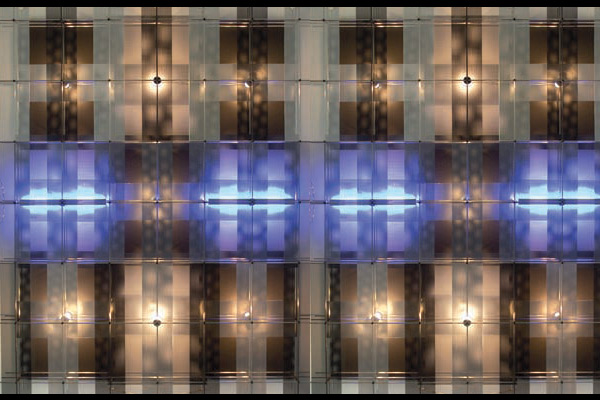

Lichtbuild #27 stainless steel, (2004) perforated anodised aluminium, xenon lamps, LED’s

He also started making spectacle frames. “I always struggled with my eyesight, I had to buy glasses anyway, and I like the look of them, [particularly] the old nickel glasses.” In 1980 he participated in an exhibition called A Case of the Spectacular with other contemporary designers, and subsequently made a series of spectacles, using gold, nickel, titanium and perspex, which again explored the theme of adjustability, often including colour or pattern. He also made rimless glasses with grooved lenses held in with nylon filament, a method commonplace today. Examples are now held at both the National Gallery of Australia and the Art Gallery of South Australia.

Lighting design in Adelaide Returning to Adelaide in 1984, Bauer took a fulltime lecturing position, teaching metalsmithing and jewellery at the University of South Australia’s School of Design. In his workshop he ventured seriously into silversmithing, producing a small series of prototypes – kettles, coffee pots and teapots – which he hoped would be produced commercially in cast iron or stainless steel. This did not eventuate. But in handraising each piece from a flat disk of silver, he further exemplified his mastery in both technical expertise and design, and many are now housed in collections.

He left teaching in 1989, (he enjoyed the students, but hated the paper work) to focus on lighting, which offered him the potential to create commercially viable products. In 1987 he had also come up with “a simple idea, but no-one had thought about it.” Instead of attaching halogen globes to tension wires or parallel tracks as was the practice at the time, Bauer developed a low-voltage support system: a two-or three-dimensional assembly of interlocking metal bars carrying, alternately, a live (uninsulated) positive or negative low-voltage charge. Globes and light fittings could be attached anywhere between two oppositely charged bars, thus offering unlimited potential, flexibility and adjustability in their placement.”I instantly went back to Europe, to a huge industrial design fair in Hannover,” where he found no other designers using the same system. He patented it. He faxed the major European lighting firms with the idea, but received only polite interest. “I lacked venture capital. I got a [local] manufacturer. He went broke.” And a couple of years later, lighting based along similar lines was released commercially and winning awards in Europe.

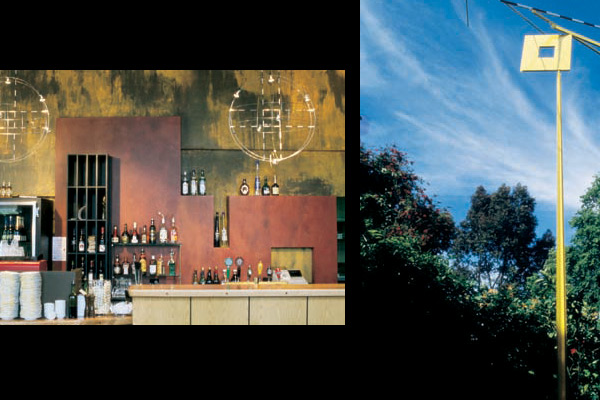

Meanwhile Bauer had found enough appreciation for his work to keep him occupied with commissions, mainly in Australia, but also from Europe and America. His work can be seen in Adelaide at the Entertainment Centre, the Velodrome, the Astor Hotel and the South Australian Fisheries Laboratories; and at Melbourne’s Southgate Project and Richmond Hill Larder & Café. He continues to develop the system and has designed pieces ranging from small table lamps and lighting sculptures to substantial architectural constructions, for which he has won two art and architecture awards from the Royal Australian Institute of Architects.

Lichtbilder and Wind Sculptures An offshoot of Bauer’s investigations into lighting has also led to what he has called his Lichtbilder series. Lichtbilder literally translates as light-pictures, but is also the German word for photographic transparencies. Intriguing, multi-layered rectilinear wall pieces, they incorporate low-voltage or LED lighting with thin sheets of perforated, often vibrantly coloured, anodised aluminium. For Bauer they have the feel of paintings. They have also been the most commercially successful of his output to date and continue to be sold through his longtime agent, Ute Rose, of Anibou in Sydney, who admires Bauer’s “uncompromising feeling for excellence” and the certainty of his vision – “he knows exactly what he wants to do”.

For the viewer moving in front of them, the Lichtbilder produce shimmering moiré effects, which have been created, says Bauer, in “homage to Jesus-Rafael Soto”. Bauer strongly believes artists should acknowledge the source of their influences. “I’m just part of a long, continuous chain, with a long accumulation of techniques and wisdom. We are always constantly building on that, and we should acknowledge that. We should give homage to predecessors.”

(Right) Patented FB Grid Lightnig System, Stainless steel, plastic, dicroic lamps (Left)Wind Sculpture Yellow, (2000) Maquette. 4 Spheres (1998)

The wind sculptures he built in 2000 saw him moving in yet another direction. These brightly painted aluminium structures – one red, one yellow – were designed as prototypes in anticipation of a public sculpture commission. The Exhibitions Curator of his 2000 Jam Factory Survey Exhibition, Margot Osborne, described them as not only incorporating “many of the themes apparent in Bauer’s work over the years – interactivity, mobility, multiple configurations, technical virtuosity”, but as achieving the most complete resolution of those themes.

Chasing the spark Bauer strives for “more than the utility and the practical aspects, it’s also to give us something to love and [to show] care and expression.” He says he is just “trying to survive. Trying to make a living. But I like to do something that has a reasonable quality. I just want to do a good job.

“There are too many products piled up on rubbish dumps. The economy is based on consumption and obsolescence – buy, buy, buy – and the next generation will have to deal with massive environmental problems. Something designed well has the potential to last a lot longer. I really believe [an object] should be of such quality that it [will] still work in, say, 20 or 30 years’ time.

“As for why I’m doing what I’m doing – I have no answer because I think it is very puzzling being a human being, full stop. Really, I’m just part of a culture. My work is just a bunch of influences. Absolutely new ideas are very rare. You’re always absorbing information, stirring it up in your own pot. Hopefully something comes out which is beyond skill, beyond visual appearance, but that sparks somewhere between all of that [with] a true personality. He mentions the Austrian writer, Stefan Zweig, who wrote about artists who achieve greatness just once in their lives, and how that ‘star hour’ validates their entire lives. “If you touched it only once, and something sparked, then it’s worth you living your life…so I’m still chasing this spark…”

Vast Terrain featuring work in aluminium by Frank Bauer, Robert Foster and Andrew Last is at the Melbourne Museum, July to November, 2005.

Portrait by Anthony Browell.

Frank Bauer was featured as a Luminary in issue #21 of Indesign.

INDESIGN is on instagram

Follow @indesignlive

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

Now cooking and entertaining from his minimalist home kitchen designed around Gaggenau’s refined performance, Chef Wu brings professional craft into a calm and well-composed setting.

Sydney’s newest design concept store, HOW WE LIVE, explores the overlap between home and workplace – with a Surry Hills pop-up from Friday 28th November.

For those who appreciate form as much as function, Gaggenau’s latest induction innovation delivers sculpted precision and effortless flexibility, disappearing seamlessly into the surface when not in use.

At the Munarra Centre for Regional Excellence on Yorta Yorta Country in Victoria, ARM Architecture and Milliken use PrintWorks™ technology to translate First Nations narratives into a layered, community-led floorscape.

Congratulations to Kerstin Thompson, 2023 recipient of the Australian Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal. We revisit Kerstin’s many accomplishments, among them being named an INDESIGN Luminary.

As NGV’s top design curators, Simone LeAmon and Ewan McEoin have big dreams for the design sector. And they’re coming at it with energy and ambition.

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

Designed by Woods Bagot, the new fit-out of a major resources company transforms 40,000-square-metres across 19 levels into interconnected villages that celebrate Western Australia’s diverse terrain.

J.AR OFFICE’s Norté in Mermaid Beach wins Best Restaurant Design 2025 for its moody, modernist take on coastal dining.