The events of this past summer have led to Australia being viewed as the global canary in the coal mine. So how might we respond to this threat to our homes and communities: both to limit further damage, and to prepare for a climate-changed future?

July 29th, 2020

As a nation, we are familiar with droughts and flooding rains, but the extreme bushfires of the past spring and summer – followed by floods, hail and dust storms in some parts of the country – have sharpened our collective attention on climate change threats.

Scientists have warned of the dangers of anthropogenic climate change – increased global temperatures caused by human activity – for decades. These include sea-level rise; acidification of the oceans; and more extreme droughts, storms and bushfires.

Last year, the Climate Council warned that “damage to property and infrastructure [would] likely to lead to painful market corrections and could trigger serious financial instability in Australia and the region .”

The events of this past summer have led to Australia being viewed as the global canary in the coal mine. So how might we respond to this threat to our homes and communities: both to limit further damage, and to prepare for a climate-changed future?

Several design experts have started exploring how cities and towns could adapt in future. Sydney-based architect and urban planner David Tickle of Hassell Studios was part of a team that developed resiliency plans for the San Francisco Bay Area, in a project funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. A second project then arose in South San Francisco, where a tech-hub and the city’s international airport are located beside the bay.

“Across government and communities, in relation to floods and bushfires, we need to ask: ‘Are we settling in the right places?’”

“Our project has been funded by grants from Caltrans – which manages the freeways – and the regional planning agency, enabling us to continue working with communities around the catchment,” David says. “It’s particularly problematic where the creek hits the bay because the area was originally swampland that’s been industrialised and developed, and – as water comes through the creek line now – it causes flooding.”

Resilient By Design, Hassell

Hassell’s design solution involves creating new green spaces along the creek line. “That helps to slow down flood waters by collecting rainwater to soak into the ground, and it creates more open space, sporting fields and playgrounds,” David says. “Projects where design can deliver multiple benefits – ecological and social resilience outcomes – create an easy win, by helping to mitigate disasters while creating better spaces.”

Hassell is now working with Australian cities and states too, especially in Brisbane and South East Queensland, where recent news reports suggested that some properties are already uninsurable . “That area is incredibly vulnerable in terms of flooding, sea level rise and inundation, because there is a fast-growing urban population,” David says.

Similar issues are impacting Western Sydney, he says, where cleared bushland and former agricultural land – the sponges of the city – are contributing to greater concentrations of water flows, and multiplier effects in big storms.

Little Elliot Island project, Sobi Slingsby

Meanwhile, on the Central Coast of New South Wales, storms in early February caused floods and inundation that left communities underwater (and without power for up to a week) placing further pressure on emergency responders after the region’s devastating bushfires.

“One promising sign in Australia is that we have greater levels of integration,” David asserts, “including better co-ordination between infrastructure, planning and open space agencies, and better disaster responses around bushfire and flooding.

“In our San Francisco project, so many people said: ‘I wouldn’t know what to do,’ but in Australia we have much better systems in place, and people know where to gather, and how to get information,” he said.

Volunteer organisations such as the RFS, SES and Surf Life Saving Clubs – and emergency broadcasts by the ABC – played a key role over summer, and will become more important as climate change impacts increase.

Last year, the Climate Council warned that “damage to property and infrastructure [would] likely to lead to painful market corrections and could trigger serious financial instability in Australia and the region .”

These growing challenges are top of mind for young architects, with two recent graduates winning major awards for design projects that tackled the issues of rising seas and water quality.

Sobi Slingsby won the 2019 BlueScope Glenn Murcutt Student Prize for her Master’s thesis that addressed the threat of climate change on the remote Lady Elliot Island in the Great Barrier Reef. It built upon her earlier research that examined three ways of coping: retreat, consolidation or adaption.

She proposed two elevated tent typologies to house scientists and researchers – one for over-water use and one for erection on land. “It’s not meant to be a solution,” she says. “It was designed to start a conversation, and it has, so that’s great.”

After completing her studies, Sobi moved to Sydney to work at Peter Stutchbury Architecture, where she is integrating her research principles with live projects. She’s also involved with Architects Declare and is keen to see further action throughout the industry.

“Each individual’s moral compass knows the responsible decision in any situation (or where to look for it),” she says, “and I don’t understand why that isn’t carried through current standards in our professional life.”

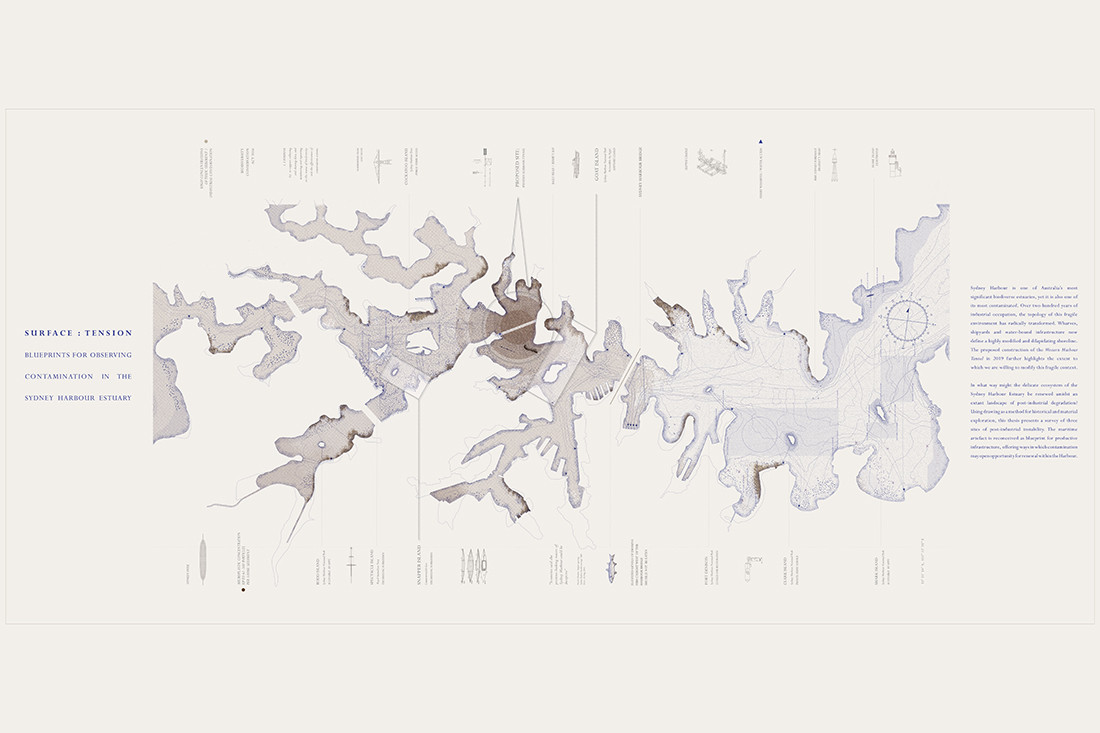

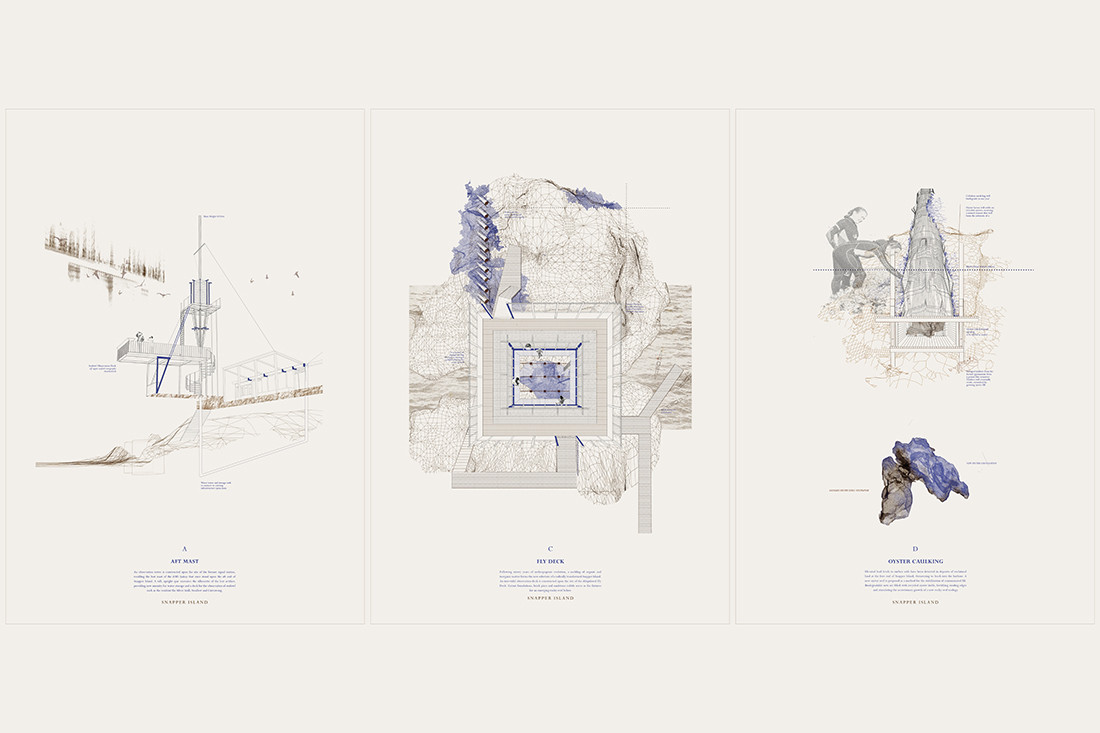

Meanwhile, Victoria King’s award-winning project ‘Surface Tension’ examines how Sydney Harbour has been altered by European habitation, and the ongoing threats it faces as the climate changes. She won the RIBA President’s Silver Medal in 2019 and is now employed at Weston Williamson, where she has been working on large-scale concepts for faster rail transport infrastructure in New South Wales.

Surface Tension, Victoria King

“It has been an eye-opening experience for me to think more deeply about the pressures we are facing in regard to future city liveability and climate vulnerability,” Victoria says. “The threat of sea-level rise has definitely influenced this work, shaping alignment options along the eastern coastline, where the most of our urban and regional population growth is occurring.

“I think that uncertainty around the impact of sea level rise will start to impact large nation shaping infrastructure development in Australia, with increased interest in how we can future proof our cities,” she adds, “In considering the future population growth of our cities, I think that we also need to start preparing for an influx of climate change refugees from neighbouring Pacific nations.”

“It has been an eye-opening experience for me to think more deeply about the pressures we are facing in regard to future city liveability and climate vulnerability.”

Surface Tension, Victoria King

Victoria also acknowledges the responsibility that architects feel to mitigate the irreversible environmental impacts of climate change. “Navigating this dilemma in both professional and personal contexts has been a challenge, but it is one that we all collectively face,” she says. “An out-of-sight, out-of-mind mentality is no longer applicable in the current climate and social context.

“Social media channels have enabled a platform for greater connectivity and that’s primarily how I have supported the great work being done by Architects Declare, who have quite swiftly mobilised collective support within the Architecture community.

Victoria adds that turning the groundswell of support into concrete actions within practice is the next challenge. “But I think it is very positive that difficult conversations about environmental responsibility are happening more frequently,” she adds. “For me, another personal priority has been to gain as much knowledge as I can about tackling climate change from outside of the design disciplines, as I think that interdisciplinary thinking and working will be the key to driving new, ecologically responsive design solutions.”

David Tickle says that his recent projects have underscored the importance of asking difficult questions, including where and how we should build in future.

“Across government and communities, in relation to floods and bushfires, we need to ask: ‘Are we settling in the right places?’” he says. “We need to move our cities and communities out of these more vulnerable areas, and yes, it’s complicated and difficult, but we have to do it. Of course we need to involve communities in understanding climate-based risks, too so we can plan and build – and inform and respond – accordingly.”

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

Savage Design’s approach to understanding the relationship between design concepts and user experience, particularly with metalwork, transcends traditional boundaries, blending timeless craftsmanship with digital innovation to create enduring elegance in objects, furnishings, and door furniture.

Channelling the enchanting ambience of the Caffè Greco in Rome, Budapest’s historic Gerbeaud, and Grossi Florentino in Melbourne, Ross Didier’s new collection evokes the designer’s affinity for café experience, while delivering refined seating for contemporary hospitality interiors.

Marylou Cafaro’s first trendjournal sparked a powerful, decades-long movement in joinery designs and finishes which eventually saw Australian design develop its independence and characteristic style. Now, polytec offers all-new insights into the future of Australian design.

Simon Liley, Principal Sustainability Consultant at Cundall, writes about how cyberpunk dystopias haven’t (quite) come to pass yet – and how designers can avoid them.

Beau Fulwood and Alison Peach on returning to a low-tech, first-principles concept of design as a strategy to combat climate change.

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

The brief for the new Government Agency office in Canberra was a challenging combination of high performance and high concept. The Mill Architecture + Design turned to Milliken to bring the ambitious project to life.

In the pursuit of an uplifting synergy between the inner world and the surrounding environment, internationally acclaimed Interior Architect and Designer Lorena Gaxiola transform the vibration of the auspicious number ‘8’ into mesmerising artistry alongside the Feltex design team, brought to you by GH Commercial.