Tadao Ando – From Emptiness To Infinity interviews and observes Tadao Ando at work, documenting the Pritzker laureate’s motivations and thinking behind his architecture into an enjoyable cinematic portraiture. Review by Yvonne Xu.

August 28th, 2014

The film opens with a suburban scene: a quiet street, linen being put out to dry on a balcony, a woman coaxing a playful child to cross the road. If we don’t pay attention, we may just miss the building standing in the backdrop – Tadao Ando’s Church of the Light.

In placing one of the world’s most iconic building in the background and side by side the sundry minutiae of ordinary life, the opening scene aligns the film with a key philosophy of Ando’s – something the architect would later in the documentary, in giving a piece of advice to a staff, articulate: ‘life and architecture belong together’. With Tadao Ando – From Emptiness To Infinity, director Mathias Frick frames just this idea by contextualising a prominent architect and his body of work for the audience. He does so at various levels, presumably to address the various interests of Ando’s wide audience and fan base.

In the fifty-two-minute documentary, Frick accompanies Ando at work in his office in Osaka as well as on a trip to Italy where some of the architect’s projects are completed or just starting. Interspersed among interviews are on-site takes of Ando’s buildings around the world, from the Water Temple in his home country to Punta della Dogana in Venice. Ando gives his interview on a handful of these featured projects, offering insight into his thinking and motivation behind them.

The camera watches how Ando interacts with people – his staff, clients, an audience of students or members of the media. This builds a portrait of the architect, and the focus is professional; it is always Ando as the architect. It observes how he works, how he mentors, what he pauses to see, how he conceptualises ideas, how he sketches, and when engaged, how he knits his brows in the deep furrow. The lighter side of the architect is captured too: at a book signing session, as he dashes off ‘ANDO’ after ‘ANDO’ on title page after title page, Ando is heard joking cheerily, ‘Only Japanese can cope with this!’

The film also watches how people respond to him, shedding light on why the architect has come to be so revered. Of note is the film’s observations of the mood and culture at Ando’s office; his staff of thirty (the perfect team size, in Ando’s view), all shod in the same white slippers, are ever on their toes, their alertness and readiness bordering on jittery. Interviews with Ando’s contemporary and fellow Pritzker laureate Peter Zumthor as well as clients (including Alessandro Benetton who lives in the Invisible House at Villa Benetton) offer interesting viewpoints, too. Perhaps most telling (and delightful) is the interview filmed in front of the pair of 4X4 House in Kobe. The unnamed man, who is out fishing, says, ‘He is world-famous! He built a huge thing in the Middle East! What was it again – in Bahrain or so. He built those two, as well. Even though they are that small, they are by Mr Ando. Despite his fame, he doesn’t solely build big things. It’s funny that you don’t know him, but after all you are not Japanese!’

Frick, who is architecture trained, honours not just the buildings but the whole atmospheric spaces Ando’s architecture creates. He effectively transports us to location, and then indulges us with cinematic observations. Ando’s bold mastery over light and shadow, for example, is depicted beautifully; and then there are the requisite panning shots that sweep over the curves of walls, as well as lingering close-ups of Ando’s signature ‘silky’ concrete. At points, a dramatic soundtrack comes on as accompaniment to move things along; but most moving are the ambient sounds that situate us in each location, locating the buildings as Ando had intentioned – always in relation to nature and the people who come to occupy each place. The cinematography is nuanced, too. As the famous story goes, Ando once hung up his boxing gloves to be a self-taught architect. An Everlast glove displayed on the office wall becomes a scene that resonates with meaning.

Overall, Tadao Ando – From Emptiness To Infinity is a rounded portraiture of the architect and his architecture, one that is just balanced enough so it is neither an inflated, fanatic tribute nor a deadening discourse.

See trailer here:

Tadao Ando – From Emptiness To Infinity is one of the twelve film selections at this year’s A Design Film Festival held from 5 – 14 September. This is the film’s premiere in Asia.

INDESIGN is on instagram

Follow @indesignlive

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

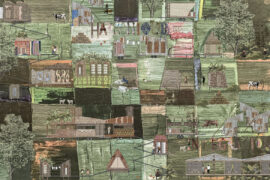

London-based design duo Raw Edges have joined forces with Established & Sons and Tongue & Groove to introduce Wall to Wall – a hand-stained, “living collection” that transforms parquet flooring into a canvas of colour, pattern, and possibility.

A longstanding partnership turns a historic city into a hub for emerging talent

For Aidan Mawhinney, the secret ingredient to Living Edge’s success “comes down to people, product and place.” As the brand celebrates a significant 25-year milestone, it’s that commitment to authentic, sustainable design – and the people behind it all – that continues to anchor its legacy.

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

Annabelle Smith has been named winner of The Graduate at the INDE.Awards 2025, in partnership with Colorbond. Her visionary project reimagines housing in Aotearoa, proposing a modular and culturally responsive model uniting people, architecture and nature.

The Standard, Singapore by Ministry of Design has been crowned winner of The Social Space at the INDE.Awards 2025. Redefining hospitality with a lush and immersive experience, The Standard celebrates both community and connection.