Singapore-based Australian architect Kerry Hill passed away on 26 August 2018, aged 75. His legacy is a portfolio of place-sensitive work produced during more than four decades in Asia.

It is with great sadness that we note the passing of Kerry Hill on 26 August 2018. Hill established Kerry Hill Architects in 1979 and ran studios in Singapore and Fremantle. He was Singapore based.

Hill received numerous honours over the years, including the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2001, the Australian Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal in 2006, the President’s Design Award (Singapore) in 2010, and appointment as an Officer of the Order of Australia in 2012 for his distinguished service to architecture – particularly as an ambassador for Australian design in South-East Asia, and as an educator and mentor. He received an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Western Australia in 2008. He was recognised as a Luminary by Indesign Media Asia Pacific in 2017.

Hill’s resorts, singular dwellings and housing, and his array of cultural, civic and institutional projects in Asia, Australia and further afield are recognisable for the meditative quality they impart. His work emerged at the point where intuition and exactitude met – where aspects of the history of architecture in a place met a vision of spatial order, climatic response, and experiences that caress the senses and clear the mind.

His work needs little by way of introduction – such is the extent of its influence and accolades. Less visible, perhaps, are the processes that shaped it and the life experiences that informed Hill’s approach.

This memorial note draws heavily on an article first published by Cubes magazine in 2014 (‘Intuition & Exactitude’, issue 70), for which Hill generously shared insights into his professional background and mode of practice.

Hill spent the early years of his life in Perth, and studied architecture at Perth Technical College and the University of Western Australia in the 1960s. At that time, a modernist spirit had begun to stir in suburb-dominated Perth, reflecting the optimism surrounding a future fuelled by the spoils of the mining industry. After graduation, Hill took a position with Perth firm Howlett and Bailey Architects where he encountered an exceptional clarity of planning and the use of modernist strategies as a springboard to the development of original design directions.

“I left Australia for Hong Kong in 1971,” said Hill during our 2014 interview at his Singapore studio, “at a time when most Australians simply flew over Asia on their way to Europe. The traditional route for young Australians was to head straight to London.” Hill’s journey emerged by chance through his search for work in the United States – a potential means of extending his experience beyond Perth. But it was a depressed time in the States. He happened to see an advertisement in an American journal for a position at Palmer and Turner in Hong Kong. Two months later, he was there.

Although moving to Asia was not entirely a conscious decision, it was entirely life-changing. Hill never returned permanently to Australia, although he opened a studio in WA (in 2005) to see through the construction of his winning entry to the State Theatre Centre of Western Australia competition. The Fremantle studio flourished thereafter with a number of civic and residential projects. The Singapore studio is located in a shophouse on Cantonment Road.

Back in Hill’s early days, however, it was an experience of Bali that was formative in terms of life decisions as well as professional development. He was sent to Bali to oversee the construction of Palmer and Turner’s Bali Hyatt, and stayed (for as long as he could) from 1971 to 1974. “Bali had an enormous influence on me,” he recalled. “There were only 100 foreigners living there and very few roads. I was practically straight out of Perth, and Bali’s singular culture astounded me. It was a very complete culture, where everything in daily life had meaning. So did architecture; it always related back to daily life, whether it was the spatial qualities of a courtyard cluster or the form of the buildings themselves.”

His experience of the planning of traditional Balinese villages and buildings – with their sequences of outdoor rooms, axial planning and courtyards – can be read in much of his subsequent work. Experiences of Japan and Sri Lanka (including the work of Geoffrey Bawa) were also formative, encouraging an appreciation of how architecture can be intimately tied to and powerfully express aspects of site, place and culture. This experience of Asia fostered an approach to ‘building appropriately’ to cultural tradition and aspiration, and architectural history.

After a period at Palmer and Turner’s Jakarta office from 1974 to 1978, Hill decided to settle in Singapore to establish his own studio in 1979 with a job in Bali from Adrian Zecha, who later founded Amanresorts and would become a longstanding client bringing many regional resort projects to the practice. Hill carried the lessons learned in Bali and elsewhere with him as his portfolio developed, blending the intuitive basis of his response to place and culture and the exactitude of rationalisation into refined planning and spatial organisation. A constant curiosity was a driver of his work – an approach surely driven by personal inclination, and perhaps also by the habit of looking with an unfamiliar gaze.

It is in the plan that the combined influence of a traditional and modern approach is most succinctly expressed. “The plan,” Hill said in 2014, “is the unifying strategy in our work. For many years, all our plans were orthogonal. I remember one day, one of my architects came running down the stairs in the studio and said, ‘You’d better get up to the top floor – there’s a curve in the office!’ But there are more curves in recent years. Our plans are changing; they’re becoming more malleable and a bit more curvaceous, but nonetheless they still have their gestation in site, in the climatic aspects of the place, in culture, and in traditional planning forms.” For Hill, the plan was the key that unlocked the idea to a scheme.

Kerry Hill Architects is known for its production of impeccable models – a form of representation with perpetuating potency despite the parallel use of digital rendering. The dedication to the time-consuming process of impeccable model construction is an apt reflection of the time spent understanding place and developing an appropriate and sensitive response through architecture.

The practice’s move into the realm of architectural competitions more recently brought new opportunities (for example, civic and cultural projects in Perth and the Royal Military College in Jordan), but in some ways challenged the well-honed processes. “Doing competitions affects the way we work, but in a stimulating way. You have to think quickly and it forces clarification of your ideas,” said Hill.

In 2013, Hill released a book through Thames and Hudson – a 440-page tome titled Kerry Hill: Crafting Modernism. At the time of our interview in 2014, it had already been reprinted and was counted as one of the publisher’s ten best-selling architecture books. The publication offers the opportunity to survey Hill’s work in, more or less, its entirety – which is otherwise a challenge given the minimal nature of the Kerry Hill Architects website.

Perhaps its most valuable pages are the two spreads of grey paper across which thirty-three plans have been placed side by side. Even without the contextualising information of land contours, landscaping or urban elements, these abstract ideograms can reveal, upon scrutiny, aspects of site and experience that will be had in the built works. Such is the impact of an architecture rooted to its place by way of planning – that aspects of its essence can emerge from representational lines printed on a page.

Our thoughts are with the Hill family and the Kerry Hill Architects community.

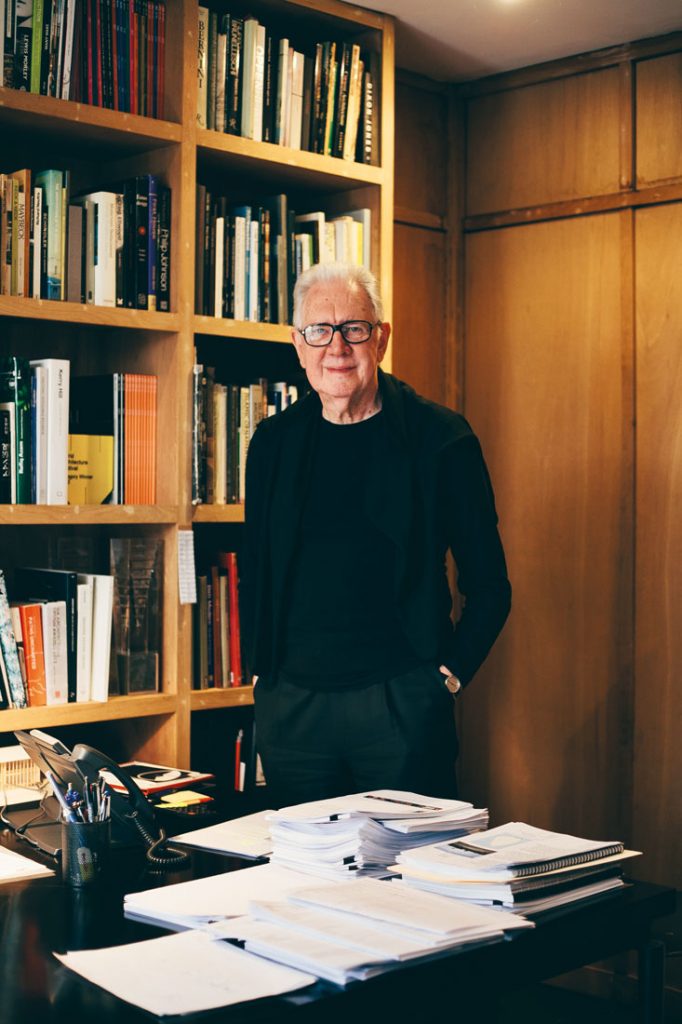

Photo of Kerry Hill in his Singapore studio taken in 2014 by Rebecca Toh for Cubes issue 70, reproduced with her permission.

INDESIGN is on instagram

Follow @indesignlive

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

In a tightly held heritage pocket of Woollahra, a reworked Neo-Georgian house reveals the power of restraint. Designed by Tobias Partners, this compact home demonstrates how a reduced material palette, thoughtful appliance selection and enduring craftsmanship can create a space designed for generations to come.

Sydney’s newest design concept store, HOW WE LIVE, explores the overlap between home and workplace – with a Surry Hills pop-up from Friday 28th November.

Merging two hotel identities in one landmark development, Hotel Indigo and Holiday Inn Little Collins capture the spirit of Melbourne through Buchan’s narrative-driven design – elevated by GROHE’s signature craftsmanship.

We republish an article in memory of the late architect by UTS, whose Dr Chau Chak Wing Building was Gehry’s first built project in Australia. The internationally revered architect passed away on 5th December.

The Australian marketing and advertising community is mourning the loss of Murray Robert Pope, a distinguished marketing strategist and community leader who passed away peacefully at his home on October 20th, 2025.

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

Mexican architecture studio LANZA atelier has been selected to design the Serpentine Pavilion 2026, which will open to the public in London’s Kensington Gardens on 6th June.

Matthew Crawford Architects and Foolscap rework Garde Hotel’s heritage buildings into a place-aware, craft-rich addition to Western Australia’s hospitality landscape.