Phillip Drew explores this year’s ‘Drawn by Design’, the bi-annual exhibition of drawings by prominent Australian architects.

April 2nd, 2014

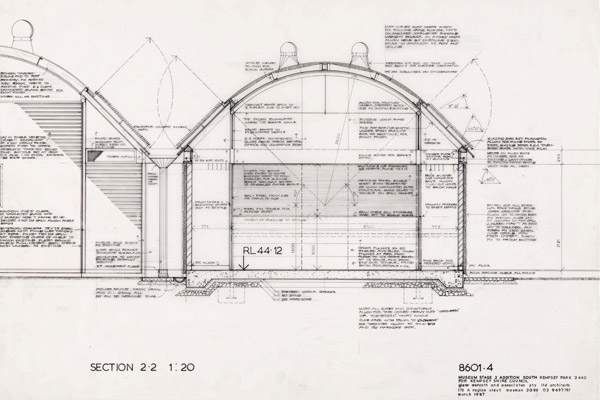

Above: Glenn Murcutt – Kempsey Museum

An American GI, imprisoned during the Korean War, spent his captivity imagining the future house he would build on his return to California. Mentally constructing his dream house stick-by-stick occupied him and kept him sane during years of solitary confinement by the Chinese. On his repatriation he built his house exactly as he had designed it in his head. This is testimony to the value of mentally rehearsing an action. Cricketers, athletes and pianists, are taught to mentally rehearse a piece of music or physical action because this is almost as effective as doing it.

When we draw, we imaginatively enact the thing itself whether it is a landscape, an existing or imagined building. Drawing is a very special activity engaging the mind in the future. Making a document on a computer by keystrokes is not the same, the connection is much more indirect and remote from the object.

Renaissance artists often went on to apply their mastery of drawing to architecture. This institutionalised the connection between the artistic and architecture which survives to the present day. One need only recall Michelangelo to witness the connection between drawing, sculpture and architecture. The bi-annual exhibitions of drawings by prominent Australian architects at Art Atrium is an opportunity to celebrate this crucial link between drawing and architecture.

Peter Stutchbury – Bungles Bungles WA

Whether the subject is landscape, in Peter Stutchbury’s evocative rendition of the Bungle Bungles of Western Australia, landscape and architecture, in Peter Ray’s magnificent Then to the Golden Temple, or architecture alone, as in Ken Maher’s beautifully sensitive street scene, Siena 78, or Cortona, images such as these do more than illustrate a conscious awareness crucial to an imaginative construction of the future. They express an attitude and suggest important values that point out a deeper orientation. Much Australian architecture in the past has been about, and reflected, the transplantation of European civilisation in Australia. Little attention was paid to noticing place or making it the source of a new sensibility. That is why the act of drawing landscape is crucial, it demonstrates attention to the here and nowbeing present instead of absent from where we have chosen to live our lives.

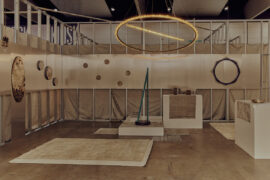

Glenn Murcutt – Arthur Boyd Centre

Drawing must remain central to design, not be a post-design rationalisation completed afterwards as instanced in Philip Cox’s watercolour of the Australian National Maritime Museum, or Glenn Murcutt’s atmospheric Arthur and Yvonne Boyd Education Centre.

Murcutt was recently quoted as saying: ”Drawing is a critical aspect of thinking.” Banning computers from his classes, the prominence of the working drawing of Kempsey Museum reflects a trend initiated by English architect, James Stirling, in the 1950s. Stirling deliberately challenged the Renaissance artist/architect orthodoxy by introducing axonometric projections to coincide with a shift towards a more diagrammatic engineering style of graphic communication.

The most notorious instance of such confusion between post- and conceptual-representations are Jørn Utzon’s sketches of the Sydney Opera Houses roofs, done years later, but mistakenly viewed as prime evidence of his concept. Nothing could be more misleading!

Drawing may also be a means of reclaiming discoveries: Malcolm Carvers Carriage House, is superb. It has more impact than any photograph, yet makes details build to a comprehensive and moody recital of a bygone reality. Drawings also honour subjects we admire. Take Rena Czaplinska-Archers Sea Ranch, sketch. You feel the raking wind, the gaunt rugged coast, the fierce exposure of Moore, Turnbull, Whitacker’s 1965 condominium apartments.

Drawing gives the architect an active direct engagement with his/her surroundings. It re-calibrates the mind and assists it in assimilating experience. As such, it is essential to thinking and design, and ultimately, in communicating to others new concepts in a manner that the computer can never compete with. Drawing is personal by its very nature, it conveys as no computer can, the unique personal vision of the drawer and has no equivalent any more than an email is to a handwritten letter.

Drawn by Design is on at Art Atrium, 181 Old South Head Road, Bondi Junctio, from 25 March to 19 April.

artatrium.com.au/exhibitions.html

Philip Drew is a Sydney architectural historian and critic. He is currently writing FRAGMENTS –

the story of Sydney from its details.

INDESIGN is on instagram

Follow @indesignlive

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

In an industry where design intent is often diluted by value management and procurement pressures, Klaro Industrial Design positions manufacturing as a creative ally – allowing commercial interior designers to deliver unique pieces aligned to the project’s original vision.

The difference between music and noise is partly how we feel when we hear it. Similarly, the way people respond to an indoor space is based on sensory qualities such as colour, texture, shapes, scents and sound.

Caesarstone’s Rugged Concrete finish delivers the authentic look of a hand poured concrete benchtop with an authentic, robust, industrial design, yet adds the refinement of modern technology.

Ben McCarthy visits what is possibly Hong Kong’s only dedicated design/art gallery and speaks with its owner, Nicola Borg-Pisani.

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

As 2026 gathers pace, Davenport Campbell Principal Neill Johanson argues that the people-place-process nexus in workplace design just won’t cut it any longer.

Record attendance, $16.4 million in sales and the debut of FUTUREOBJEKT signal a fair confidently expanding its cultural and commercial reach.