Every decision we make as architects and designers from the very first moments of project conception has carbon consequences.

January 24th, 2022

Many years ago, I was in Los Angeles when I spotted a project that had won an architectural prize. Unlike most of the prize winners, this project stood out to me because it was not a completed building at all, but a ruin. The architect had cast his project 100 or 1000 years into the future and his concept was strong enough that, even as a ruin, it resonated as an undeniably beautiful piece of architecture.

I often say that architecture is not eternal. Carlo Ratti explored its very impermanence at Milan Design Week in 2019, growing Gaudi-esque arches from mycelium with the express intention of returning them to the earth once the Salone had ended.

When I think of plant-based design, I think of Ratti’s Circular Garden. I think too of Israeli designer Erez Nevi Pana using five tonnes of salt byproduct from the Dead Sea to craft building blocks for the NGV’s Triennial earlier this year. And then, I ask myself, are we getting ahead of ourselves?

The potential of mycelium, of replacing traditional building materials with plant-based alternatives is heartening and hopeful, but it is also fanciful. The latest report from the global authority on climate change, the IPCC, has been called a ‘code red’ warning. It projects that we will pass 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming within the next decade or two, and draws a clear link between human activity and the increasingly extreme weather events.

Buildings generate nearly 40 per cent of annual global greenhouse gas emissions.

As architects and designers, we are not ignorant of this and yet, we remain complicit. The best of us consider the sustainability of our buildings in operation, but that is only part of the equation.

More energy is expended during the production of materials than at any other point during a project’s life cycle. It is no longer acceptable for us to be unaware or uncaring about the impact of building our buildings. Nor can we turn a blind eye to what happens to our projects when their lifespans inevitably come to an end.

While researching, I came across Silo, a London restaurant designed by studio Nina+Co and fitted out with sustainable materials that could biodegrade or be disassembled for repurposing in the future. It reminded me of one of my own projects from 2019, a 191-square-metre zero waste pop-up restaurant on the top level of the Lexus Design Pavilion.

Dubbed Paperbark, it was one of our smallest projects, both in scale and budget, and featured a ceiling adorned with over a kilometre of repurposed biodegradable fabric that curved and enveloped guests. While simple in geometry, the façade was an example of the sustainable framework that should underpin all hospitality design. After the event, Paperbark was donated to local universities, but it could have just as easily been recycled or composted.

A restaurant is the perfect forum to experiment with a more circular, zero- carbon design process. It presents in a smaller, more relatable scale that can then be applied to a much larger agenda. It’s also the sector that requires the most immediate attention. A 2006 Centre for Design report estimates the lifespan of restaurants and shop interiors to be five to 10 years.

Wouldn’t it be nice if all those tables and chairs, those ceiling and wall panels, floorboards and interior finishes were made of plant-based materials?

Yes, but wouldn’t it be even nicer if they could be saved from the landfill all together? If they could be refurbished or recycled? Or if we could simply extend their lifespan to more than half a decade?

The former is something to which we can aspire. The latter is something we can do right now. Every decision we make as architects and designers from the very first moments of project conception has carbon consequences.

The 2019 Ellen MacArthur Foundation report, Completing the Picture: How the Circular Economy Tackles Climate Change, found that 45 per cent of emissions come from producing the products we use every day. We cannot transition to a net- zero carbon reality overnight, but we can start holding ourselves and our practices to a higher degree of scrutiny.

Ask your suppliers simple questions like: ‘How sustainable is your manufacturing process?’ ‘What and how much packaging do you use?’ ‘Do you have a take back program?’ These are the first steps towards implementing a more circular bioeconomy.

The latest IPCC report has proven we don’t have the luxury of waiting for plant-based design or some other silver bullet to save us from the climate crisis. To date, there isn’t significant legislation in place mandating us to be better, but that is even more reason for us to step up. We can’t solve the problem alone, but we can, as leaders in the construction industry, have a real impact.

Architecture, like food, benefits greatly when we slow the process down, when we consider our products and our methodology carefully. And when we, like that architect in Los Angeles, spare a moment’s thought for what will be left to the generations to come when we, like our buildings, are no longer standing.

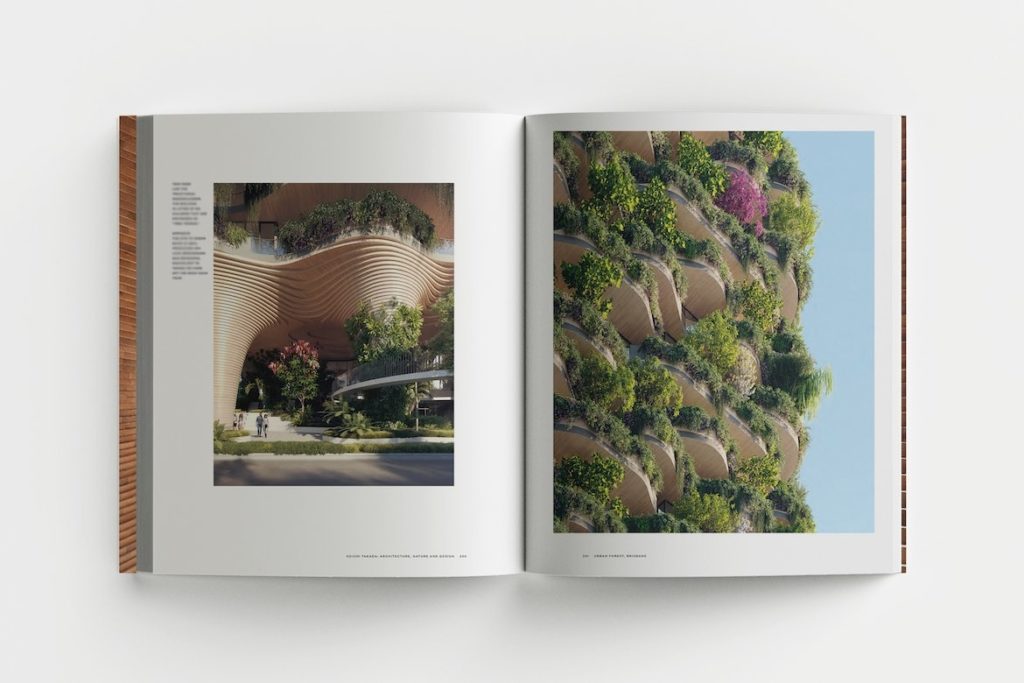

Read more about Koichi Takada in his new book, KOICHI TAKADA Architecture, Nature and Design.

Koichi Takada Architects

koichitakada.com

This article originally appeared in Indesign Magazine #85. Order your copy today.

INDESIGN is on instagram

Follow @indesignlive

A searchable and comprehensive guide for specifying leading products and their suppliers

Keep up to date with the latest and greatest from our industry BFF's!

Now cooking and entertaining from his minimalist home kitchen designed around Gaggenau’s refined performance, Chef Wu brings professional craft into a calm and well-composed setting.

Natural stone shapes the interiors of Billyard Avenue, a luxury apartment development in Sydney’s Elizabeth Bay designed by architecture and design practice SJB. Here, a curated selection of stone from Anterior XL sets the backdrop for the project’s material language.

At the Munarra Centre for Regional Excellence on Yorta Yorta Country in Victoria, ARM Architecture and Milliken use PrintWorks™ technology to translate First Nations narratives into a layered, community-led floorscape.

In an industry where design intent is often diluted by value management and procurement pressures, Klaro Industrial Design positions manufacturing as a creative ally – allowing commercial interior designers to deliver unique pieces aligned to the project’s original vision.

KFive kicks off a year of 25th anniversary celebrations with an intimate in-conversation about ‘comfort’, at the Melbourne Art Fair.

FK’s Nicky Drobis takes us through a recent poll of 1,000 office workers across Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane that suggests a preference for reuse – despite an ‘awareness gap’.

Byera Hadley Scholarship-winner Michael Jones is about to set off on a research trip across five countries. He tells us why his research focus, straw, is a sleeping giant in the context of climate crisis and built environment waste.

The internet never sleeps! Here's the stuff you might have missed

KFive kicks off a year of 25th anniversary celebrations with an intimate in-conversation about ‘comfort’, at the Melbourne Art Fair.

The final tower in R.Corporation’s R.Iconic precinct demonstrates how density can create connection — through a 20-metre void, one-acre rooftop and nine years of learning what makes vertical neighbourhoods work.