In the mid-1960s, he was the first Australian architect to achieve a high level of international recognition, especially in North America where he was seen as an American architect working in the then fashionable ‘brutalist’ style. But John Andrews has at times been less comfortable in Australia where several signature buildings have been treated with less respect than they deserve. Indesign thought it time to celebrate one of the icons of Australian architecture.

“In Canada in the sixties, I was flying,” says John Andrews. His first major project, Scarborough College at Toronto University, was much awarded, included in the New York Museum of Modern Art collection and, thanks to some cunning manoeuvring on his part, featured in the international edition of Time Magazine. Canada was booming and the success of Scarborough College set the tone for his career over the next ten years. In the United States, his Gund Hall, Harvard Graduate School of Architecture won more acclaim. In 1970 he returned to Australia, but the substantial body of work he created in North America was capped in 1980 when he won (“unanimously”) an international competition to build the Intelsat Headquarters building in Washington, D.C.

Story continues below advertisement

His best-known buildings in Australia (and his most controversial) are the Cameron Offices in Belconnen, ACT, and King George Tower (formerly the American Express Tower, now NRMA Tower), Sydney. But there are many more across the country: the Convention Centres in Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney and numerous educational and campus buildings, offices and housing schemes.

Both here and in North America Andrews became known for forceful, large-scale building projects, for re-thinking accepted practices and ‘fighting the fight’. The demands on architecture were changing rapidly and Andrews offered unequivocal solutions. The man has been described in similar terms to his architecture: big, bold, burly and rugged. Thoroughly forthright, he confronts challenge with an intense, boots-and-all determination. A book co-written with Jennifer Taylor, which charts the first two decades of his career is sub-titled Architecture a Performing Art, as Andrews appreciates the significance of the two distinct architectural roles he plays. “One is actually getting a project done so it’s capable of being built, on time, on budget; the other is selling it, the straw hat and cane routine.”

Particularly in Canada, where he played up his ‘Australianness’, his confidence, candour and bullish bravado worked well for him. “I’m not a design luminary. I’m just a guy who liked doing what he was doing. I don’t sketch or draw or paint. I don’t design furniture. But I make buildings better than anybody I’ve ever known.”

Story continues below advertisement

Scarborough College, University of Toronto, Canada. Photo by David Moore Photography ©.

As a kid, Andrews was practical by nature and good with his hands. The family business in monumental masonry had “gone kaput”. Times were tough. “I spent most weekends working with my father, lopping trees, doing odd jobs, making things.” Later, working briefly for a builder, he learnt about carpentry and developed a respect for the craft of building. “Building was the thing. Architecture just seemed like a good thing to do.” ‘Buildability’ became a fundamental determinant of his design work, an integral part of the logical process that led to the form of his buildings. (“I firmly believe there’s too much bullshit in architecture. You’ve got to be able to build.”)

Story continues below advertisement

Through his university years he worked part-time at Edwards Madigan Torzello, where in 1956, his final year, he produced the firm’s submission for the Sydney Opera House design competition. “I developed a bunch of steel and glass boxes. But just to see what Utzon did with the same brief – this marvellous, flowing thing – was probably the most salutary lesson I ever learned. It made me stop and think: there’s something else.”

Graduating with Honours, he applied to several US Master Programs (MIT, Harvard, Penn, Columbia). “I had no doubt that when I graduated I wasn’t a bloody architect. I didn’t know if it was the right thing to do, but at least it was more. I was literally grasping at straws.” He chose Harvard because it offered a (fee) scholarship. Short of cash, but with no lack of chutzpah, he also applied for a (living allowance) scholarship from Sydney University, which favoured children of ex-servicemen gassed in WWI. “I thought: there can’t be too many of those – and I got the scholarship because I was the only applicant!

Cameron offices, Canberra. Photo by David Moore Photography ©.

“Harvard had a big reputation. Gropius had retired a couple of years before, but a Spaniard, Josep Luis Sert, was there. Jesus, was he something else! He believed in a lot of social values related to architecture. He’d worked for Le Corbusier. He was into housing. It was the most exhilarating time I’ve ever experienced!” Andrews credits Sert as one of the major influences on his work. “He taught me a great deal – that architecture is very much to do with common sense, that a building is a solution to a problem, that you can’t solve a problem unless you know what it is.”

Louis Kahn was another formative influence. “He said, you have to find out what a building wants to be – that became a very basic philosophy for me. You’ve got to refer to who’s going to use it, who’s going to build it, where it is, what it’s supposed to be. You establish your own brief.”

While he was at Harvard, Andrews, with three other students, worked on a proposal to design Toronto City Hall – “the next big international competition after the Sydney Opera House.” His submission, selected (along with one from I.M. Pei) as one of six finalists out of 500 entrants, didn’t win, but it was highly regarded and job offers in Toronto followed.

In 1962, having set up on his own after four years with one of the big firms, he had little work, mainly kitchen renovations and model-making. “I was broke.” He took a teaching job at the School of Architecture at Toronto University and when the management suddenly discovered it had drastically underestimated the facilities required for the future, it rushed headlong into planning a new off-campus college. With most of the staff away on the summer break, Andrews was asked to join a small team to evolve a master plan for the site. Instead, within six weeks, the three men presented an overall design proposal and somehow persuaded the university to go with it. Within months, with Andrews as architect and a large firm handling documentation, construction on Scarborough College had begun. The speed of the process was breathtaking. In the flurry of the moment the 29-year old Andrews had seized the opportunity of a lifetime. “It was just pure luck,” he says. “The right place at the right time.”

Left: Canadian National Tower, Toronto, Canada

Right: King George Tower, Sydney

Scarborough College is often regarded as Andrews’ finest work, expressing his main architectural concerns in a dramatic and spirited form. Those concerns, defined early on, have remained consistent throughout his career. Along with issues related to building process, site and environment, they revolve around an intuitive response to planning for human needs, with a particular focus on traffic flow, climate control and public spaces – all aimed at promoting human amenity and social interaction. As a result, he designed Scarborough College not as a series of independent faculty buildings as expected, but as one continuous, open-ended structure with internal streets. It was a masterstroke that set a planning precedent. Andrews might say it was purely common sense, but the accolades and publicity the project attracted pushed his career into overdrive.

Projects at Expo ’67 in Montreal, shopping centres, university colleges and student residences ensued. One of these commissions was for 1,760 student residences at Guelph University, Ontario, a ‘dorm-city’ made up of ‘economic enclosures’ where he confronted the human need for individual identity within such en-masse schemes. While the mood of the time hankered for high-rises, Andrews, opted for a walk-up solution. He fought the battle, and won. Here, as elsewhere, his notable use of geometry, another fundamental element in his repertoire, brought order and cohesion to the extensive, low-rise plan.

In 1968 another major opportunity presented itself. He was commissioned by the President of Harvard to design a new building to house the Graduate School of Architecture. “It occurred to me later, that Josep Luis Sert wasn’t going to have [it designed by] one of Gropius’s students – who by that time were all big names like I.M. Pei, Victor Lundy, Paul Rudolf.” Sert had pushed for one of his own, although he soon retired and the project was left somewhat rudderless. Student unrest was rife and the process fraught, although it remains, particularly for Andrews, one of his most significant achievements. “To be selected to do it, and to have it survive – I’ve got a son who’s an architect, who graduated in my building – I’d have to be proud of that.”

In the 12 years they spent in Canada, Andrews and his wife Ro had four sons, and Andrews was keen to see them grow up in the same way he had: to have contact with nature, develop practical skills and be resourceful. He was tiring of the harsh Canadian climate, worn down by student tensions and by “the constant bloody battle – people trying to drive ten tonne trucks through specifications,” when he was offered the job to design the Cameron Offices in a new satellite suburb outside Canberra. The family returned to Australia, to Palm Beach, where Andrews set up a new practice. A few years later the family also bought a farm at Eugowra, in mid-western NSW, where the boys could experience rural life. “We’d cut down pine trees and made sheds. I enjoyed teaching them to build. Some years later he designed and built a house there, an innovative re-take on the Australian farmhouse tradition, where he has been “more comfortable than I’ve ever been anywhere in my life.”

Cameron Offices was precisely the kind of project Andrews enjoyed. “It was the biggest job ever built in Australia at the time – a million square feet – it was a city not a building! And I’m much more interested in the building as part of the city, in the urban forms of things, than I am in the individual gem.”

Briefed to build five 15-storey buildings to accommodate 4000 public servants, he persuaded the National Capital Development Commission (NCDC) to create instead “something that was people-oriented, that had the fabric of a city, with main streets and back alleys and gardens.” Like many of his other projects, it was stepped down the slope, providing shade for the offices, but allowing sun into the courtyards. Again, instead of a series of single buildings, he produced a compact, integrated, pedestrian-oriented urban environment – and created the only example of structuralism to be found in Australia.

Then came King George Tower. “That’s the first building ever built in this country that took serious notice of what the sun did. Most of the sunshades in Sydney were concrete things stuck on the side of buildings that heated up like a torch, retained the heat, and radiated it into the building.” Andrews’ solution was to attach sun shields, made from an extremely light, thermally inert polycarbonate material, to a three-dimensional filigree framework on the outside of the building.

By the mid-1970s he’d re-established himself in Australia and was much in demand. In 1980, he was a juror on the Parliament House, Canberra competition. Then he won the prestigious Intelsat project, and was again flying regularly back to North America, as well as overseeing his busy practice here. In 1983, King George Tower was awarded the RAIA’s Sulman Medal. In the same year, Andrews underwent five-way heart by-pass surgery, but recovered well and got back to work.

The Andrews farm at Eugowra in mid-western New South Wales.

By the late-1980s, however, recession had hit again and in 1990 he closed the Palm Beach office. Later, as expectations of landlords and tenants in city office buildings steadily increased, King George Tower came under attack. Amid much controversy, and despite being acknowledged as a significant marker of the style and environmental concerns of its time, it was extensively re-modelled (by the Rice Daubney Group.) Amongst the many changes made, it lost its trademark sunglasses. “That nearly killed me,” says Andrews. “Why would an architect take another man’s building and change it without talking to him? Why would he even accept the commission? They did some good things. They fixed up the entrance. But it was recognised as one of the most significant Australian high-rises, and then it got ruined. Gone.”

An even more ignominious fate seemed imminent for the Cameron Offices. While they, too, have gained high recognition – they’ve been listed on the Australian Heritage Commissioner’s Register of the National Estate, and on the RAIA’s list of Significant Twentieth Century Architecture – two-thirds of the complex was slated for demolition. A Government spokesperson claimed the offices were ‘dysfunctional and did not meet health and safety requirements.’ Part was sold privately for residential development, but fortuitously, when an intermediary established contact between Andrews and the developer, a plan was hatched to save it. “I pointed out that (apart from costing a lot of money to demolish) it absolutely lends itself to housing as it is.” For the past year Andrews has been working with architects and the developer to re-fit the offices as apartments. “It’s certainly one of the most exciting things I’ve been doing lately,” he says. (He has also been farming red deer and has developed substantial vineyards from which his own wine is produced.)

With the Cameron Offices as a case in point, the irony in Andrews’ work is that his main motivation has been to create buildings that elevate the human experience. Yet he acknowledges that they “are sometimes more powerful than you’d expect them to be. The humanism is somehow subjugated by the strength of the geometry. I had a chance, at a fairly early age, to do a lot of big things.” (Big projects = big problems, he’d said earlier.) “And I worked very fast. I’m not known for my sophisticated details. It’s more about getting it done than about making sure every nut and bold is in the right place,” he says.

The output from his offices has been substantial, but his legacy is hard to pin down. Even he rejects the usual classification of his work. “I’m not a modernist. I’m a rationalist. I believe in appropriateness. Each time I came up with a design solution I believed it was the right answer, the appropriate answer.” In the process, he has undoubtedly made a significant contribution to architecture on two continents, with landmark buildings that bear the forceful stamp of his commitment, individuality and temperament. They remain eloquent proclamations of their time.

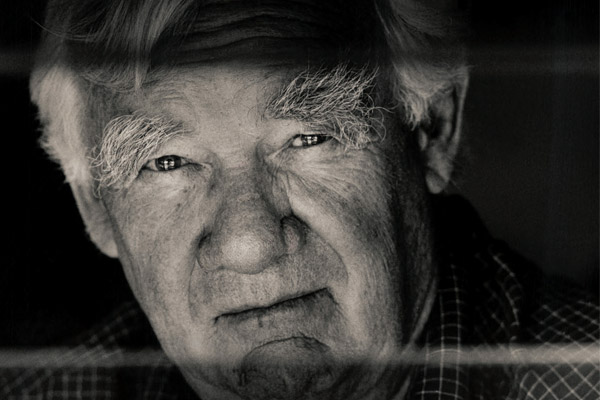

Portrait by Anthony Browell.

John Andrews was featured as a Luminary in issue #12 of Indesign, originally published in February 2003.